As Health Canada begins releasing tests capable of identifying who among us has unknowingly been exposed to COVID-19, many might be wondering: Was that coughing back in March really COVID-19?

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said this week he intends to be tested once the antibody tests become broadly available. “I will certainly ensure that I’m one of them,” said the PM, whose wife Sophie tested positive for COVID-19 earlier this year after returning from a trip to the U.K.

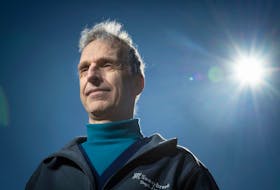

Two antibody tests have been authorized for release under a federal interim order and many companies are working furiously to produce more of them. On the surface, Dr. David Naylor seems less-than-enthusiastic about their ability to predict if an individual is protected from COVID-19: “For now, there’s an awful lot of uncertainties that argue for real caution in their deployment.”

It might seem an odd statement coming from the co-chair of a national task force struck a month ago to oversee countrywide use of the tests. But questions around immunity remain among COVID-19’s great unknowns.

Also known as serological tests, antibody tests can identify who has been infected and developed antibodies, or proteins. The tests look for past, not active infections, and can offer a clearer picture of the virus’s spread. The true number of infections in Canada are believed orders of magnitude higher than official case counts. Université of Montréal economists estimated that Ontario has 18 times as many cases, and Quebec 12 times as many as reported — close to half a million people in the two provinces alone.

“What we can say, broadly speaking, is that a positive test means there’s a very high likelihood that the person was infected with the virus at some point in the last few weeks or months,” said Naylor, a professor in the faculty of medicine at the University of Toronto, in an email exchange.

However, even if antibodies are present, “we still don’t know for sure that the antibodies signal strong protection against another COVID-19 infection,” Naylor said.

Also not clear is how long immunity lasts — long enough to bridge people to a vaccine? A few months? Given the uncertainties and the fact the virus can cause “a very serious and potentially fatal infection in very meaningful numbers of people, it’s risky to use these results to give advice to individuals,” Naylor said.

“Where this information is more immediately valuable is in knowing where we are in the Canadian course of the epidemic.”

Serosurveys, where researchers collect and analyze blood samples, can provide a clearer picture of how much the virus has circulated undetected in different regions and populations. The first early estimates of “background immunity” could be available within weeks.

Randomly sampling households, or blood donors, or big-box shoppers, for example, could address questions around “herd immunity,” which occurs when enough people in a population have antibodies to an infection to stop it from spreading. With COVID-19, it’s been estimated the threshold for herd immunity may kick in somewhere between 55, and as high as 82 per cent of the population.

Naylor said it’s a mug’s game to try to guess what proportion of the population in Canada has antibodies to the pandemic virus. A “back-of-the envelope” calculation suggests a three per cent background immunity “isn’t implausible,” he said, based on the number of confirmed cases to date — 85,000 as of Monday — and a ratio of at least 10 undetected cases to every confirmed case. That would still leave an unnerving number of people susceptible.

Antibody testing also isn’t just a “one-and-done” scenario, Naylor said. Background immunity would need to be checked intermittently as cases crop up and the number of people exposed increase, he said.

Serosurveys could also inform decisions on where and whether to relax physical distancing. “It’s not likely to drive a binary yes-no lockdown decision,” Naylor said. “But that type of information might help communities and worksites determine how they manage risks and how stringent their risk mitigation strategies must be.”

It could also give a much clearer picture of COVID-19’s true infection fatality rate, meaning the ratio of deaths divided by the actual number of infections, not just confirmed ones.

U.S.-based Abbott expects to begin shipping its antibody tests to Canada this week after receiving Health Canada authorization. The Italian-made DiaSorin LIASON test has also been green-lighted by Health Canada.

Specific groups, such as health-care workers, will be targeted first. “It’s not yet sort of prime time for regular use to inform individual decision making right now,” said Dr. Theresa Tam, Canada’s chief public health officer. The goal is to test more than one million Canadians over the next two years.

Initially, when a person is infected with a virus, the first antibodies on the scene are IgM antibodies that appear within a week of infection. Later, a more durable antibody, IgG, is produced and detectable after about two weeks. The Abbott and DiaSorin tests detect IgG antibodies.

What’s not known is how long the antibodies last in the blood of people who were exposed, what level is needed to be protective and how strongly the antibodies neutralize the virus, said Anne-Claude Gingras, co-leader of a team of researchers at Sinai Health System and the University of Toronto that has developed an antibody test.

Seasonal coronaviruses that cause the common cold don’t elicit long-lasting immunity. But SARS-1 did. Immunity lasted over years, Gingras said. “We hope that this new coronavirus will be more like SARS-1.”

Copyright Postmedia Network Inc., 2020