By Ossie Michelin

Special to The Telegram

A year has passed since I was in Labrador MP Yvonne Jones’ office in Ottawa.

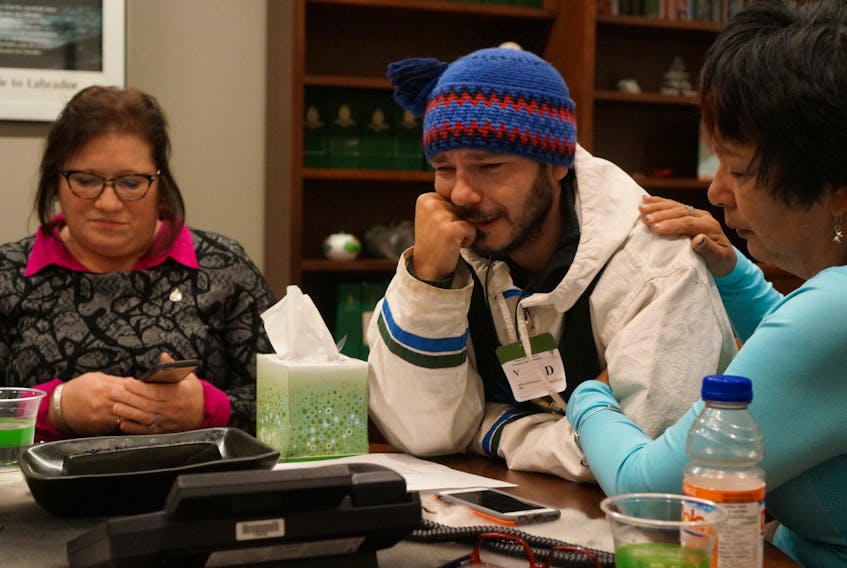

I was with friends in our nation’s capital, pleading to government to hear our concerns over the Muskrat Falls hydroelectric project. It was after midnight and we were all waiting on news from the talks between the three Labrador Indigenous leaders and the province over environmental mitigations at the Muskrat Falls project.

Those of us who were still eating had ordered pizza. We carefully chose to eat it in the hallway down from Ms. Jones’ office, because inside, Billy Gauthier, Jerry Kohlmeister and Delilah Saunders were on a hunger strike, and even though they said they enjoyed the smell of food, you couldn’t help but feel twinge of guilt eating in front of them. Billy, alone, had lost 21 pounds at this point. We could all see it was taking a toll.

I’ve talked to people in Happy Valley who say they lie awake at night thinking their homes and families could be washed away from this earth. We were afraid, too, of our democracy being eroded.

Soon we got a call from the province’s representative telling us all the demands of the hunger strikers had been met after hours of negotiation. My friends could eat again.

We felt like we were on top of the world. We felt like we had won an important battle in the war to save our way of life, food and future in Labrador. We were overly optimistic. We thought that the word of our premier, Dwight Ball, actually meant something. We thought a public declaration would be enough to hold off on construction of the dam while important environmental testing, mitigation and monitoring work could be completed. We were desperate, exhausted and pushed past our limits; the province no doubt realized this and pushed forward their agenda. They agreed not to raise water levels and to seek out and remove the contaminants before flooding.

It has been a year, and as the dam construction continues, none of these promises have been delivered.

While the dam’s runoff is in the shared harvesting area of Lake Melville, the falls themselves lie within the Innu land claim. For inking the contract on Muskrat Falls, they were promised a desperately needed new school that wasn’t full of mould, new houses for the exploding population, recognition by the federal government of a Labrador Innu homeland, and an apology for driving out the Innu from Central Labrador for the Smallwood reservoir.

Let that sink in. The Innu were desperate from decades of abuse and neglect from provincial and federal governments, and the province used this promise of a decent standard of living — which they already should have had — in exchange for signing off on this monstrosity. I do not blame them one bit. What’s a bit of contaminated fish in exchange for having running water and a warm house?

It is deplorable that the province and federal government used this as bargaining chips to get what they wanted.

For years, as concerned citizens and Indigenous people, Labradorians repeatedly told the province and Nalcor that we were scared of this dam. We were scared that it would pollute our prime food source of Lake Melville, we were scared that this would cleave us away from our culture, our way of life, the way of our families and ancestors. We were afraid that we were not being listened to. We were afraid that science was not being listened to. We were afraid of the stability of the bank. I’ve talked to people in Happy Valley who say they lie awake at night thinking their homes and families could be washed away from this earth. We were afraid, too, of our democracy being eroded.

Muskrat Falls makes Labrador feel like a colony of Newfoundland and not an equal partner in this province. We feel like nothing more than a provincial suffix — “and Labrador” — that claims ownership of our land rather than equality. We felt that no matter what we did, no matter how right we were, no matter how much proof we had that this was going to damage us, this project would go ahead. At no point in the history of the Lower Churchill Project were we afforded the right to say no.

How can I have faith in my democracy when there is only room for endless debate and no room for action to correct the problems we all see? How can I believe in government when they promise they will do the work to protect us, to make us feel safe in our own land, only to have them change their minds? How can I believe in reconciliation when our Indigenous rights are not being heeded? How can I believe any of this when it took my friend losing 21 pounds from a two-week hunger strike just to have what we thought was a real negotiation with our elected officials?

After Muskrat Falls, my province is weaker, my home is damaged, my culture is threatened, my food security is lessened, my democracy has been undermined, my press is less free, my government is less transparent, and I’ve never seen the people of my home more divided.

Many have told me they see this project as a yet another injustice to Indigenous peoples, or a blatant disregard for environmental science, but for me and those in my community it is a lot more simple: we want to keep eating our fish and seals. We want to continue our way of life. Contaminating our fish and seals with methylmercury is doing more than just impacting our food security — it’s casting doubt on our culture. It’s making us question if the best food we have available to eat locally right now will make us sick in the future.

I implore the Islanders reading this: imagine if you could have seen the exact events of the fisheries collapse coming. Imagine if you fought to protect those fish for future generations and you were denied at every step by the people you elected into office. Imagine if you won that fight and you were able to save the fish, save the Newfoundland way of life.

The mercury from the Muskrat Falls is our fisheries collapse. It is the event that will cut us off from who we are. I am asking you, as a Labradorian, please help us. Please help my family and my community. Labradorians are such a minority in this province that we need strong voices in Newfoundland to tell government this is not how a democracy functions, that the people of Labrador have agency and the right to say no.

It is not too late to put this project on hold and to ensure that environmental damage is to a minimum and human health is championed. With this project, we, as Newfoundlanders and Labradorians, can be leaders and set a new environmental standard for the world.

Or we can keep doing what we always do and apologize later.

I’m sick of apologies. I want to Make Muskrat Right.

Ossie Michelin is a journalist and activist from North West River, Labrador, and a proud Labradorian.