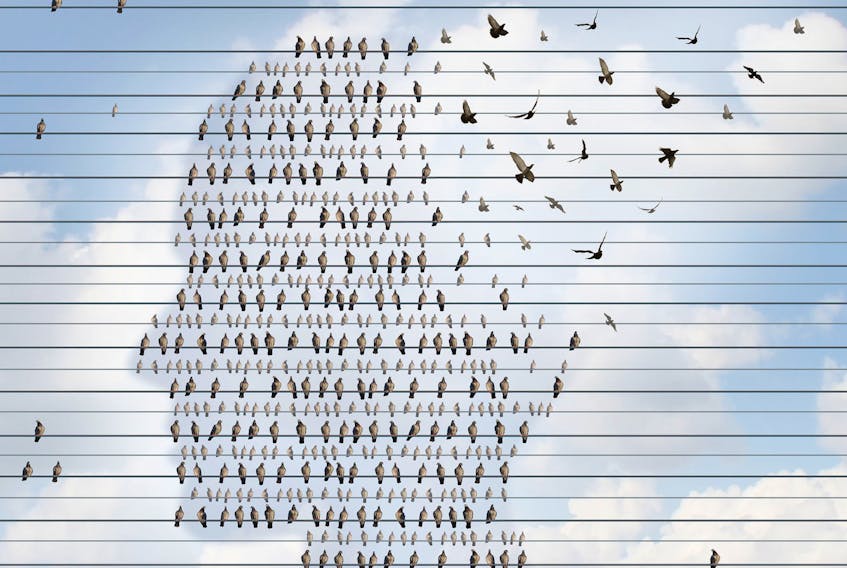

“None of us wants to be reminded that dementia is random, relentless, and frighteningly common.”

— Laurie Graham, British novelist, whose husband has dementia

If you’ve known anyone with dementia, you know just how cruel and indiscriminate it is. It can rob memory, change personality, wreak havoc with spatial awareness, kill all recollection of important milestones in life, numb the senses.

There are more Canadians living with dementia than there are people in Newfoundland and Labrador and P.E.I. combined — 747,000 according to the national dementia strategy, which was formalized via legislation in 2017. That number is expected to double in 20 years as more baby boomers join the ranks of those afflicted.

It primarily affects older people, though we all know shockingly young exceptions to that rule.

Dementia is a spectrum, with Alzheimer’s being the most commonly known of the brain diseases it encompasses.

It may surprise you to know that women are twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than men.

The ratio is 2:1 worldwide, says Dr. Gillian Einstein, a researcher with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) who specializes in women’s brain health and aging. In fact, one of the reasons why she became interested in her area of expertise is that when she was with Duke University Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, she noticed a decided trend among the brains she was studying.

“I was studying the brain pathology in Alzheimer’s disease patients and it began dawning on me that most of the brains I obtained at autopsy were women's brains,” she wrote via email, adding that “woefully little was known about women’s brains” at the time.

Einstein is studying whether the interaction of estrogen loss after menopause and a particular gene variant in women might make them more susceptible to Alzheimer’s.

“The risk factors for men (besides aging) seem to be different: dramatic brain injury, cardiovascular disease,” she explained. “Dementias more common in men (but still present for women) are Parkinson’s dementia and fronto-temporal lobe dementia.”

It can rob memory, change personality, wreak havoc with spatial awareness, kill all recollection of important milestones in life, numb the senses.

For all of us, the key to staving off dementia is preparing our brains as best we can. It’s something we can target with school curriculum.

Dr. Yves Joanette is scientific director of the CIHR’s Institute of Aging, and chairman of the World Dementia Council.

He said the first plan of attack should be to treat brain health like heart health, as both organs benefit from the same things: good nutrition, healthy exercise, a strong social network.

Phase 2 of preparing your brain involves building up a “cognitive reserve.”

“You can push back those diseases by keeping the brain strong, by keeping your brain active doing new things,” Joanette told me in a phone interview from Montreal.

He said while many people know the benefits of reading, doing word puzzles or brain teasers, one of the best things people can do to keep their brain nimble is to speak more than one language a day.

“It is one of the most efficient ways to create some kind of protection,” Joanette said. “If everybody in Canada — and this is not a political statement — spoke both official languages every day, it would be the best thing they could do.”

He says Canadian research is making important strides in the study of dementia, including the research of Dr. Ana Inés Ansaldo of the Université de Montréal into the benefits of bilingualism.

In an interview with the Montreal Gazette in January 2017, Ansaldo explained her findings, saying that “After years of daily practice managing interference between two languages, bilinguals become experts at selecting relevant information and ignoring information that can distract from a task.”

In other words, their brains learn to work more efficiently, keeping more cognitive power in reserve for when it’s needed.

Joanette says people can keep their brains limber in other ways, too, by learning to do things outside their comfort zone.

A dance enthusiast could learn woodworking for example, or an auto mechanic take up calligraphy.

“Probably we know more about the moon and Mars than we do about the brain — it’s a complex, mysterious organ,” Joanette says. “But there are indeed good things happening.”

Related Pam Frampton columns:

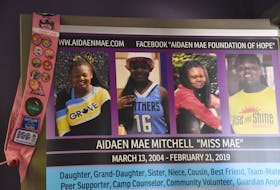

Kaleidoscope — fragements of memory

Pam Frampton is The Telegram’s associate managing editor. Email [email protected]. Twitter: pam_frampton