The opening page promises: “This book is for St. John’s.”

Indeed, the city is more than a backdrop, but a supporting actor to the central character of Sophie.

Sophie writes, or tries to write, or wants to try. She spends a lot of time in bars, particularly The Levee, sometimes screening herself from fellow patrons with Jane Austen novels. She is haunted by her mother, and careens between two men, Sal and Henry.

The action sometimes geographically shifts to Montreal; the duplexes with their circular external staircases; the metro stations. But Sophie’s natural habitat is downtown St. John’s.

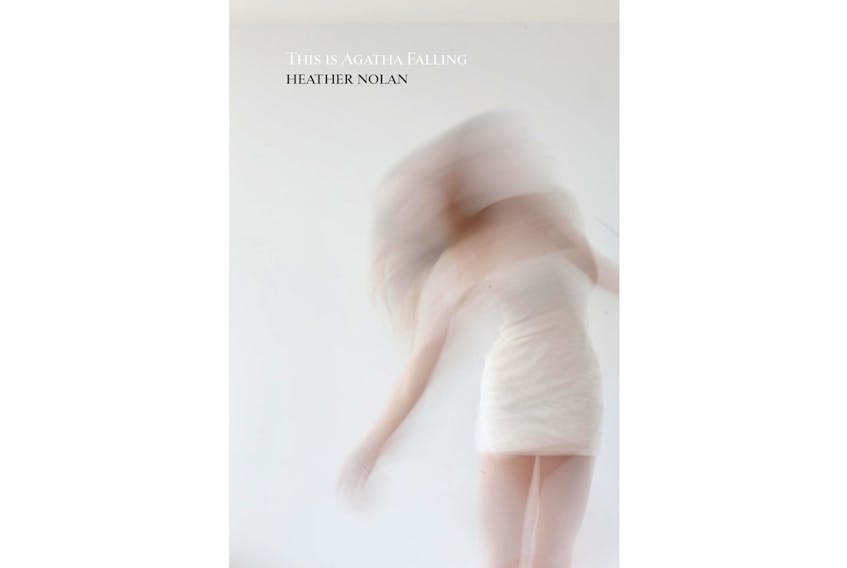

“This is Agatha Falling” (the title derives from a fictional hurricane) is Heather Nolan’s debut, a slim volume of a novella composed of interlinked vignettes. Novella in its Italian origin means new, but has come to apply to a specific length of prose; both meanings neatly dovetail here. Nolan has published poetry and also works in photography, an interest perhaps not coincidentally reflected in the visual elements and even the shape of her work.

The chapters are short, often two or three pages, formatted by sections of simply a sole proper name – “Henry” – to a single to a dozen or so paragraphs. Chapter titles – “What Woke Sophie,” “She Had Begun To See Her In Mirrors” – are often repeated in the text: “The sun glinting on the frosted window was what woke Sophie early, crystals thick and sharp, sending prisms of light staggering through the room.”

The drama plays out in scenes, over a year or so, with flashbacks. Sophie’s life, her worries and her potential, seems caught on a couple of hooks involving her parents, and the repercussions they cast over her own decisions.

“Back before any of it, when Sophie and her mother and father and brother and sister were all in the van headed somewhere, there was a fight. There was always a fight. Sophie’s father was driving, carefully, trying to keep the peace. Siblings were yelling about which radio station to turn on, their mother unwavering. They were going to listen to the Anne Murray tape she had brought.”

Musical taste is the least of it – Sophie’s mother is a focal point and an uncomforting, uncomfortable figure.

“What Sophia remembered was her mother sitting in that brown rocking chair with the dog on her lap. A cutting bitterness to her voice, saying, Your father only ever cared about his own family. Cared about his mother more than me. The way her mother spat the word father. The way her ten-year-old brain slowly processed this, trying to decipher who the enemy was.”

Another question though is how reliable a narrator is Sophie? She has deliberately mis-named at least one person, and recalls events, sometimes obsessively, but her recollection can turn. Questions of identity and memory consume her, but she knows she’s not on sure ground there.

“Recently, while thumbing through a magazine in a grocery store check-out, Sophie had read an article on memory. How the brain stores your last memory of an event, your last recollection of an event, and each visit to this memory changes that data very slightly. Replaces it. This shook Sophie quite a bit. Mostly it shook her because it made her wonder if dreams and illusions were both stored in the same place. If she recalled the memory of a memory, and the memory of a dream, would these two new memories then live endlessly altering in her brain? How would she determine which was the memory and which the dream?”

Recollection may be slippery, but there’s a tactility here as well, impressions gritty and granular, with not just texture but traction.

“Her most vivid memory was of that day they returned from Twillingate. In the car on the ride home, when her mother said no to an ice cream stop, and Sophie had sulked, her mother said. Do you want to move back to your father’s, is that what this is all about?

‘Sophie said, I hate it here. I hate living with you.

“Back at the house, a cabin in the woods heated only by the birch they chopped together out back, she heard her mother make a sound. A sound like waves of broken glass scraping against a rocky shore.

“Sophie knocked on the bedroom door. The sounds did not change. Slowly, she turned the knob, eased the creaky door open. There was her mother, lying in the centre of her bed, still wearing her jacket, curled in fetal position. She made no move, no twitch, when Sophie entered the room.”

Such suspensions tie the events together, prick by prick.

With “This is Agatha Falling,” Pedlar Press continues its record of quality publications, significant works in thoughtful design, down to the thickness of the paper.

Joan Sullivan is editor of Newfoundland Quarterly magazine. She reviews both fiction and non-fiction for The Telegram.

Previous column: