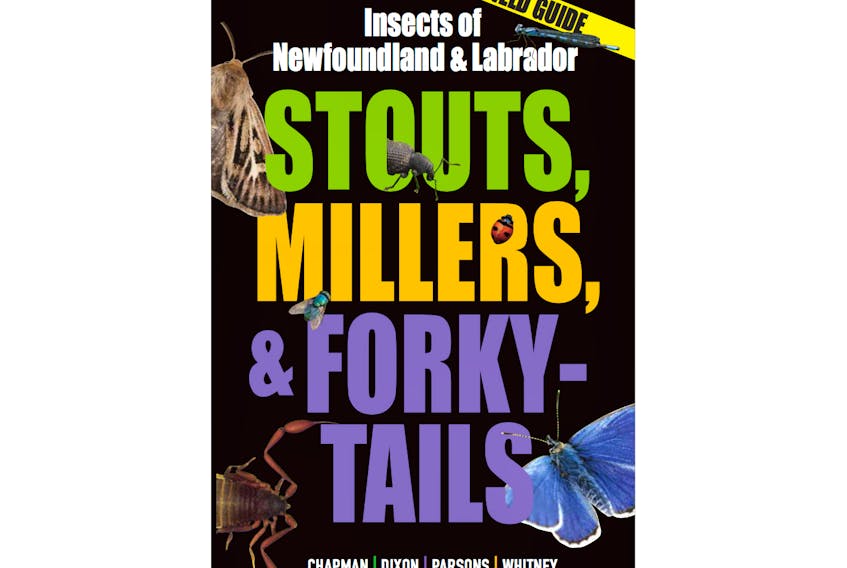

If you already have an interest in insects, this field guide will be jam for you. Not only is it densely informative, it’s also colourful and well-organized and of a nice, pliable heft.

If you, like me, have ever quailed at the sight of a centipede, regularly responded to a wasp by flailing your arms and veering off a sidewalk into moving traffic, and more than once wondered what insects were “for” anyway, this is also the book for you.

Here’s a starter fact: “Approximately 1 million species of insects have been described to date. Are there only million on the planet? No way.”

And they are “for” a bunch of stuff. “Insects are models for studying physiological, behavioural, ecological and evolutionary phenomena”; they “play significant roles in the functioning of almost all terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems” and “can also inflict immense harm on humans and other animals as vectors of disease.”

“Insects are destructive” as well as “essential to our food security.”

The formal study of insects in Newfoundland and Labrador dates to 1766, when “Joseph Banks and his friend Constantine Phipps (both born into affluence) arranged passage from Great Britain” to “reveal the natural history of the region.” (During this trip, Banks was introduced to Capt. James Cook.) Then, in 1827, Philip Henry Gosse arrived in Carbonear from England. Employed as a clerk, his passion was entomology and he identified and painted (beautifully) many insects; in fact he was recognized as “the foremost natural history author of his time” as well as possibly inventing the saltwater aquaria “— all agree that he popularized the hobby.”

Current provincial expertise is found in, if not exclusive to, Memorial University and the Newfoundland and Labrador and federal governments, as reflected in this quartet of authors, described as “a retired provincial veterinarian, two applied entomologists, and a professor of entomology.”

They open with a basic definition: “What is an insect? To the public, insect, ‘fly,’ and ‘bug’ are often used interchangeably.”

Specifically, they “are arthropods, but so are crustaceans, arachnids, and the extinct trilobites. An arthropod is a member of the animal kingdom that has jointed legs, an exoskeleton, and a segmented body.”

The book is sorted into 18 categories, for example “Hymenoptera//Ants, bees, wasps,” “Neuroptera//Lacewings,” and “Odonata//Dragonflies, damselflies.” These are further denoted by colour stripes across the top of the page — “Lepidoptera//Butterflies, moths,” for example, is purple. Common names are listed with the scientific (Latin) names and other common names, along with “Habitat Icons” such as “People/pets,” “Garden,” “Wilderness” and “Water.”

Short, crisp paragraphs set out the insect’s appearance, how they feed, and the regions or continents where they’re found, among other data. A fact box provides “at-a-glance information on size range, habitat details, and distribution.” And there is at least one, and often many more, full-colour photos, like the arresting full-page portrait “Face of a male modest masked bee.”

A sample entry includes: “The confused flour beetle, ‘Tribolium confusum,’ was given its name because it was confused with a similar species, ‘Tribolium castaneum’ (red flour beetle), for many years. The two can only be distinguished as adults with the aid of magnification of the antennae. Adults of the species were found in jars containing grain in the tombs of pharaohs around 2500 BC and can still be found infesting grain today. … Female beetles can lay 300 to 400 eggs over a period of five to eight months. Thus, the introduction of a few beetles can create quite an infestation in a short period of time. Careful sanitation, regularly cleaning cupboards, and storing flours and other cereals, bran, dried fruits, seeds and beans in containers, can prevent a major infestation.”

Traditional song lyrics referencing one or another insect are also occasionally featured.

“Stouts” includes a glossary, Index (by scientific and common names), recommendations for further reading, and an excerpt from Tom Dawe’s poem “Alley-Coosh, Bibby, and Cark”: “D is for dows’y poll, / Moth of the night; / He sloos at my window / In search of the light; / Some call him a miller, / But where is his mill? / He seems far from home / When he lands on my sill.”

The title, by the way, refers to deerflies, moths and earwigs. Earwigs, even more than wasps, are my bête-noire. Is there anything positive I can learn about them? Well, “they do have wings but they rarely fly.” That’s … good I guess?

Joan Sullivan is editor of Newfoundland Quarterly magazine. She reviews both fiction and non-fiction for The Telegram

RELATED: