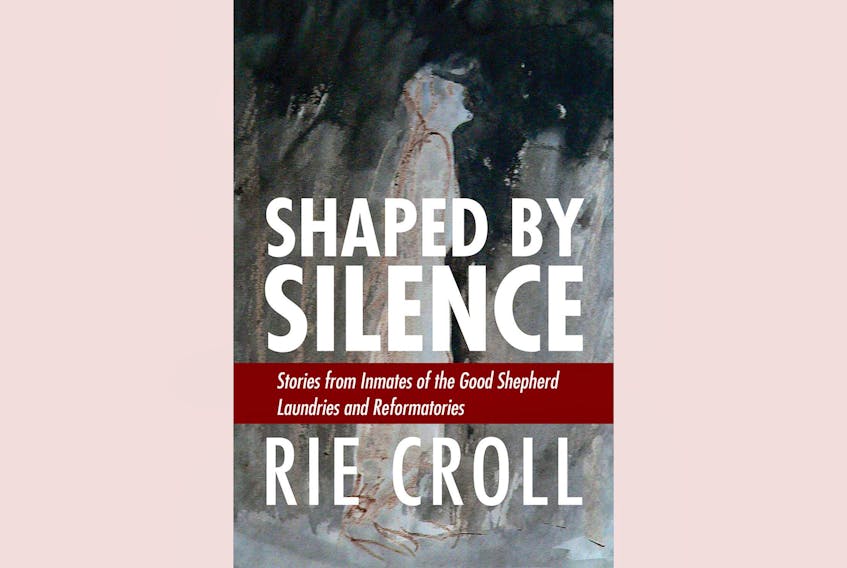

This volume consists of the stories of five women, from Canada and Ireland and Australia, “whose lives were shaped by forced confinement in Magdalene laundries and related reform ‘schools’ operated by the Roman Catholic Order of Sisters of the Good Shepherd.” One was a teenager in training school in Toronto, one was born into the institution, and three were sent to the laundries in Ireland and Australia; all their experiences happened between 1930 and 1960.

In her introduction, sociologist Rie Croll thoroughly lays out the Good Shepherds’ history, ideology, and ultimate goal of “Making Compliant Women.”

The Good Shepherds “was founded ‘only to receive girls and women, who, have fallen into licentiousness.’”

The objective of these “reformatories, laundries, homes, asylums, training schools, convents, refuges, and monasteries?” “Physical labour, isolation from unseemly forces, and prayer were a large part of the nuns’ strategy for converting their charges into the Christian image of pure womanhood.”

There were other such initiatives. For example, the Irish “Magdalene homes,” which predate the Good Shepherds, and had a somewhat similar goal. But women entered the Magdalene homes voluntarily (admittedly that term does not tell the whole story). Those within the Good Shepherd were sent there by external forces.

For example, Chaparral Bowman. In the early 1950s she fled the Good Shepherd Reformatory and Industrial Refuge Laundry in Saint John, N.B. She “climbed through an unbarred second-story window, crossed the reformatory’s internal yard, and scaled a beam that supported the high fence enclosing the institution.”

She was 18, and had been born inside. She first lived on the streets, stealing food, and then became a prostitute, living with other women in a brothel.

She didn’t know how to cash a cheque. She didn’t know how to cross a street.

“She would wait for groups of people to gather and then cross the street with them, even if they were moving in a direction that initially took her out of her way.”

The nuns had originally intended, or at least promised to, find an adoptive home for Chaparral. Periodically the children would be dressed up and lined up in front of prospective parents. “I was probably five and she came and stopped by me and she said, ‘Mrs. B, what about this little one?’ And she had her hand on my head and I remember I was praying ‘let me be adopted’ … I didn’t even know what adopted meant.”

In contrast, in Australia, in September 1967, Rachael Romero, 14, was sent to the Home of the Good shepherd in Adelaide, known as “The Pines” “for one year of hard, unpaid labour.” Her crime? She had repeatedly run away from home. Her mother, a runner-up for the title of Homemaker of the Year, “chose to have Rachael committed … rather than bear the indignity of making her father’s abuse public.”

At The Pines the women were subjected to a complete erasure of self – they were even renamed. (Rachael is the name she picked, with The Old Testament spelling.) Though there were between 70 and 80 other inmates, it was a lonely place, and cruel: solitary confinement, constant belittlement.

Half the world away, in New Ross, Ireland, 12-year-old Maureen Sullivan arrived at what she and her mother had been told was a good school. She had schoolbooks and a new pencil case. But instead of studying she was inducted into labouring alongside adult laundresses. She was so little she had to stand on a box to reach the equipment. She also had her name changed, to Frances. “If you didn’t answer to it, [the nuns] would come down and pull your hair, and punch you or box your ears … they wanted you to catch on to that straight away … you see, I wasn’t Frances. And I wouldn’t answer … You know, when your ear is sore and your hair is pulled, and your head is sore, you’ll answer.”

She was the only child inside those walls. “That anomaly became a key point in her later struggle to have the state take responsibility for what happened to her as a child. ‘That was a hard battle to wage,’ because she met with a wall of denial; she was repeatedly told that there were no children in the laundry and that, therefore, she could not have been a laundry inmate.”

“Shaped by Silence” gives such troubling and formerly hidden narratives a voice.

Joan Sullivan is editor of Newfoundland Quarterly magazine. She reviews both fiction and non-fiction for The Telegram.