Ada and Evered Best (the names are as calibrated as everything else) are the titular “Innocents.” When they are still very young (they are not exactly sure how old they are, maybe Evered is 11, Ada nine), their baby sister, Martha, and then their mother, Sarah, and father, Sennet, die within weeks of each other. It is just into the new year, winter.

“They were left together in the cove then with its dirt-floored stud tilt, with its garden of root vegetables and its scatter of outbuildings, with its looming circle of hills and rattling brook and its view of the ocean’s grey expanse beyond the harbour skerries. The cove was the heart and sum of all creation in their eyes and they were alone there with the little knowledge of the world passed on haphazard and gleaned by chance.”

Their exact location is not given, but they seem to be to the northeast, on a route towards Fogo. The nearest is outport Mockbegger; neither of the children has ever been there. The only other person they have seen in Mary Oram, a midwife from Mockbegger, “an imp of a figure, no taller than Ada, dressed in clothes made of calico and wool and a colourful knitted hat on her bald head.”

The horizon of their entire world is how far they can move on foot or by small boat, and its air infused by the dictates of sheer survival. They can only eat what they catch or grow, just as they can only wear what they make (although salvage might factor into both contingencies). And they can only perform these tasks as they’ve gleaned from their parents, who, while they certainly expected Evered and Ada to work (and Ada to help deliver her sister), had not readied them for fully adult responsibilities.

There is no way to contact anyone (and nobody they know to reach, excepting Mary Oram, who spooks them) until “The Hope” sails into the cove on its regular routine.

The family, like all who prosecute the fishery, lives by credit, the truck system, profits and losses added up in the merchant’s ledger. Aboard the ship is Abraham Clinch, known to Evered as “The Beadle,” with the near magical power of not only allotting supplies and evaluating the fish, but also noting births and deaths. Since the loss of the Reverend he’s also performed weddings and prayers for the dead. (All the adults that come into the children’s lives have an agency and knowledge that renders them mysteries to the brother and sister: they can write, hunt, navigate their way to exotic places.)

Clinch reads prayers over Martha’s grave, and, against his first instinct, agrees to supply Evered, and their lives become seasonal rounds of (often brutal) labour: the caplin, followed by the cod, and, as time permits, planting and harvesting the root vegetables in the garden. In the spring there might be seals. At the height of the summer they eat supper standing up because they fear falling asleep if they sit down.

While Ada and Evered are affixed in the cove, they are not alone.

Author Michael Crummey has described this “almost like a road movie.” The sea carries the traffic to them. Indeed, even before they can both remember, they’d had a visitor, “the Stranger” who washed up dead on their shores, and is buried near the garden. Their only clue to his identity is a beautiful silver button Ada unearths, her special treasure.

Crummey has also discussed how the siblings did not have a childhood, and in the sense that they worked harder than I (for example) ever would or could, that is true – but they are still responding to, interpreting the world around them, as children. They set to their subsistence like adults (as best they can) but think, imbue, forecast as according to their years. Ada takes the time and space to create a kind of folk art, gathering and arranging found objects of curiosity and allure. She also engages in mental communion with her beloved little sister, keeping her present with a lyric inner dialogue.

That, I think, is their innocence, and like all innocence it is doomed to be lost. The cove may be far from a Garden of Eden (or might not be), but the intruder, sexual awareness and knowledge, is the same.

If you are aware of the genesis of this book, and thought it might be a bleak read, think again. Really think again.

This is beautifully written and often quite funny.

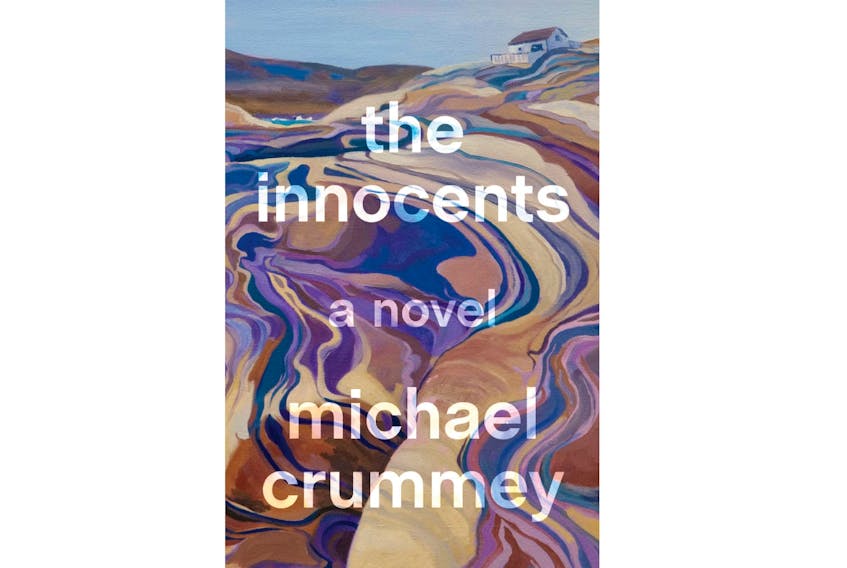

This is Crummey’s sixth novel (and I think his shortest one?) – and not coincidentally he’s also a poet with five volumes to his credit, and that skill imbues his prose. I’d also like to note how the gorgeous cover image (by Diana Dabinett) aptly illustrates Crummey’s embedded passion for his landscape.

Joan Sullivan is editor of Newfoundland Quarterly magazine. She reviews both fiction and non-fiction for The Telegram.

RELATED: