Milton Ontario, born and bred in Saskatchewan “in the absolute middle of this absolutely flat nowhere,” was designed and destined for “an absolutely average life.”

Some junior hockey, a possible romance with one of his school’s seven Ashleys, and eventual employment welding or pipefitting at a work camp or industrial site.

But then an unforeseen and very specific set of circumstances alters the split-level-bungalow, heavy-equipment-operator trajectory of his life. In junior high, a substitute teacher, a sophisticate who “owned the only Volvo in all of Saskatchewan,” introduced Milton to the work of Leonard Cohen. And Milton decides he will become a poet.

Milton’s poetry is … not good. That doesn’t stop him.

In fact he pursues this goal with fantastic drive; fueled by near-constant listening to “I’m Your Man,” he writes and writes.

A steady stream of heartbreak poured towards the unheeding figure of one of the Ashleys. A specially bound volume submitted, completely inappropriately, for a class assignment. Immediate fame is imagined, but the actual results are zilch.

Yet Milton is undaunted.

He will be a poet and the first step, obviously, is to move to Montreal. From his part-time job at Uncle Randy’s Farm Supply he saves up a minimal stash of funding, rents a room in an apartment “sight-unseen from Craigslist with three strangers,” and gets on a bus.

It’s the middle of winter. He knows prairie winter. But he’s never experienced a Montreal winter.

“The wind whipping off the flueve is like being hit full force in the face with a boat paddle.” Then the door of the bus station also smacks him in the face. Additionally, he’s not quite sure how to get to avenue de l’Épée from the bus station. His ill-preparedness sets the tone for his beleaguered debut in the city.

But Milton is nothing if not dogged. Neither his filthy, hectic apartment nor lack of employable skills daunt him.

Guided by his roommates, two of whom don’t actually live in his apartment, he plunges into Montreal’s art scene, a continuous cycle of readings and openings and moveable art and puppet shows, with potlucks of vegan dumpster cuisine consumed by “freegans, anarchists, Anglophones studying Russian at Concordia, and young marketing executives.” On such a night he meets Robin, who provides the arc to the narrative, as well as its title.

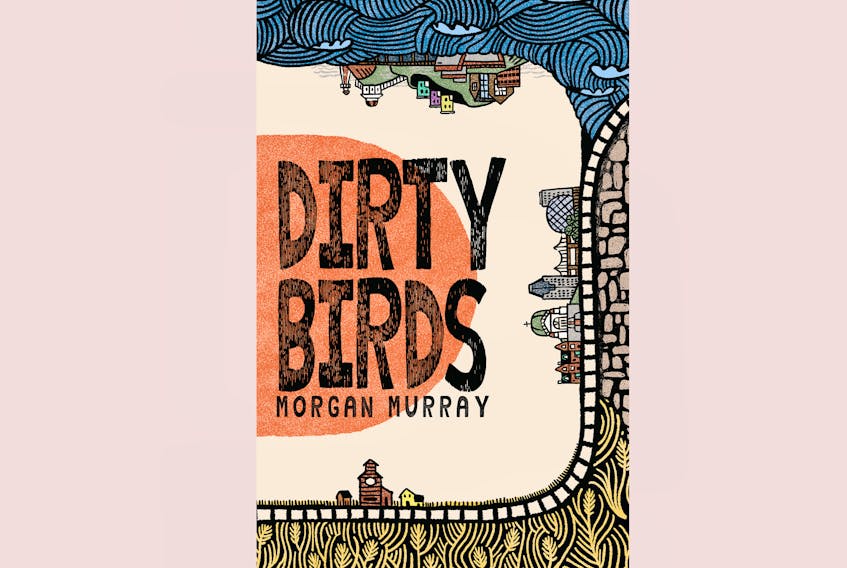

Robin is a filmmaker whose short documentary, “Dirty Birds,” filmed over three years in India, features the landfill gulls of Calcutta.

She explains, somewhat impatiently, that it’s “an elaborate allegory … I want to give these birds agency.”

She goes on; it’s all over Milton’s head, but he doesn’t care. He is in love.

Though the path to romance is not a smooth one, Milton does start to find his feet in Montreal; this comprises a good chunk of the book.

But then he’s knocked off course by some under-thought shenanigans.

Without spoilers, events carry Morgan to St. John’s, a basement bedroom in the Battery, and a sinecure as a graduate student in biology.

There, he is immediately embroiled in a controversial battle to have seagulls, a fellow grad student explains, “declassified as seabirds and reclassified as terrestrial birds.”

To ornithologists, them’s fighting words, as a subsequent post-debate melee proves.

So, lots of exuberance here, lots of satirical whimsy.

One cover blurb compares Murray to Vonnegut (maybe it’s the drawings Murray has liberally salted through the pages), but the tone doesn’t quite strike me that way.

It is energetic and fantastic and also happily incorporates the author himself in a skewed kind of way (which I think Vonnegut did), but he also does this with real life figures (which I don’t think Vonnegut did do).

Most strikingly is the boldness (audacity?) of employing Leonard Cohen, both as the actual revered cultural touchstone as a poet and a musician which he is, and as a thoroughly fictional criminal mastermind known as “the most dangerous man in the world.”

One of the most fun and dynamic aspects of the book is Morgan’s facility with different dialogues. These include, but are not limited to, the matrix of the prairie junior hockey structure, the non-stop conversation of a Newfoundland taxi driver, academic papers, police files, and, most prominently, Milton’s poetry.

These are often decoded and/or annotated in footnotes, a comedic amplification that’s an effective and refreshing device in this fiction.

There’s work and care in the writing; the experiences, however foolish, feel earned.

At the same time it’s kinetic: the words, like birds, take flight.

Joan Sullivan is editor of Newfoundland Quarterly magazine. She reviews both fiction and non-fiction for The Telegram.