One counterintuitive facet of “tradition” is that it is not something set in stone, but is as fluid and un-static as the moving, current world. Preserving traditions takes active story upkeep and can be controversial, as opposed to completely accepted, lore – for example the Screech-in – which we will not discuss at this time.

“The Portuguese Waltzes” are widely known as coming from the accordion of Art Stoyles, but how they came there in the first place is something of an enigma. In Richard Sima’s “Mystery,” Tamara is trying to learn to play the accordion, with the goal of winning “Accordion Idol.” Among her audience is Art, who lives in a senior’s home, next to her grandmother. He encourages her to play, though he usually falls asleep before she works through a tune. Tamara knows Art is famed for his accordion playing, and of his association with a piece of music known as The Portuguese Waltzes. She asks her father:

“So, where did those tunes, ‘The Portuguese Waltzes,’ come from?”

“Nobody is really certain, but this is the story I heard … A long time ago, when the fish were plentiful, the Portuguese crossed the ocean every year to fish the Grand Banks …”

The White Fleet stopped visiting St. John’s harbour decades ago, but Tamara’s father remembers it. “The whole city smelled like fish in those days. Boats from all over the world came to port, but it was the Portuguese we locals loved most. Groups of fishermen wandered the streets in their coloured checkered shirts and home-knit sock caps, looking at shop windows and chattering away. They bought postcards, nylons for their wives, and toys for their children. I was much younger than Art, but I remember kicking soccer balls around with them. For fun, the fishermen would toss us into the fishing nets just like we were their own kids.”

To perform, and to achieve her competitive goal, Tamara must conquer her own shyness. Art, too, faced challenges – he never went to school – but musically he was a prodigy, and that gave him heart. When the White Fleet were tied up in the harbour, he would play for tips.

So Tamara writes Art a letter, asking for his secret. Where did the waltzes come from?

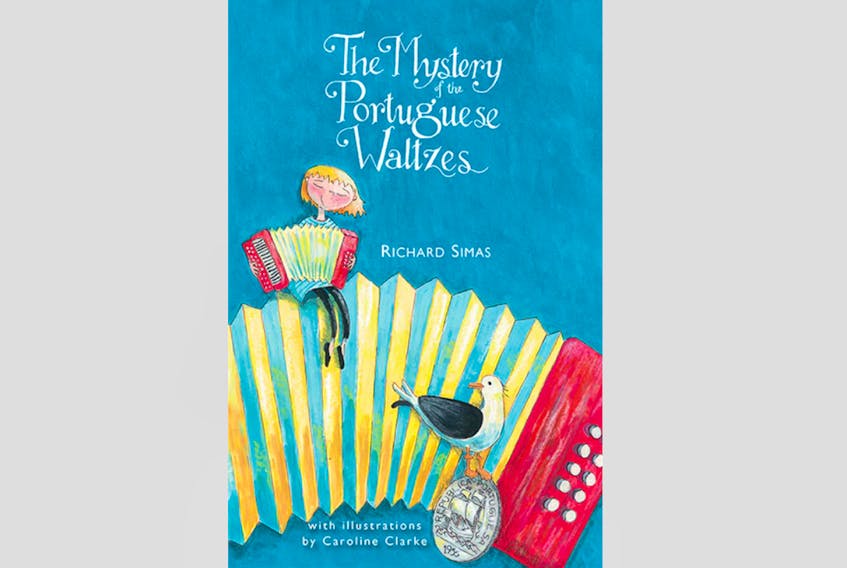

In accompaniment to this musical puzzle, Caroline Clarke has a light, sketch-y touch with her imagery, especially the views of vintage downtown St. John’s.

2019 was the UN International Year of Indigenous Language, and “Nutaui’s Cap” is an impressive initiative: “The Labrador Innu speak two dialects of their language Innu-aimun. In this text the Sheshatshiu dialect is presented first, followed by the English and finally the Mushuau dialect.” (The book also includes a “Backgrounder,” a map, and a dictionary:“ituteht they go somewhere on foot.”)

Nanass is 10, and has been camping for two months with her family. Today is the day she will learn to fish.

“Nutaui (my father) grabbed his well-worn blue Innu Nation ball cap on the way out. The Innu flag on the front showed the world where he belonged.”

The expedition is a success, the namesh (fish) fried and consumed.

But then: “Without warning, a deafening boom drove us to the ground, even Nutaui. I heard my heart pound hard against my chest. Seconds later another ear-splitting blast struck us. I screamed and ran to hide in the tent. Nikaui and Nukum (my grandmother) ran after me.

“‘It’s the jets,’ Nikaui said holding me tight, her eyes showing her fear.

“‘They were so low,’ I said, ‘they almost touched the trees. The animals must be afraid too.’”

It was the military conducting low-level flying, bombing tests in a range that included Innu campsites.

Nutaui called a meeting of all the Innu elders.

“‘Canada is not listening to us. We will walk on the airport runway so the jets will not fly.’

‘Can I come too?’ I asked.

‘The young and the old must all walk.’”

Together they climbed the fences and blocked the runways. They were taken away in buses, but came back. They set up a protest camp, with wood stoves and woven bough floors.

The police said they were trespassing.

“‘This is Nitassinan, our homeland,’ Nutaui reminded him.

People get arrested, including Nutaui. As he was placed in the police car, “his Innu Nation ball cap fell into the dirt.”

Nanass collects it; a comfort and a talisman. Now perhaps the hat is becoming part of her family memory, her tradition.

As a visual parallel, Penashue’s artwork evocative in line and palette.

These lovely publications are in good keeping with Running the Goat’s commitment to producing quality children’s literature.

Joan Sullivan is editor of Newfoundland Quarterly magazine. She reviews both fiction and non-fiction for The Telegram.

RELATED: