“Today I remember a garden party,” this book begins. “My memories come from the mid-1970s, when I was a little girl and very impressionable. Inside the Lodge, a game of bingo occupied a line of tables which would soon be set out with cloths, cutlery, and desserts – confections much fancier than the ordinary home-baked goodies we were used to, for everyone knew that ‘food prepared for the church’ would be extra special.”

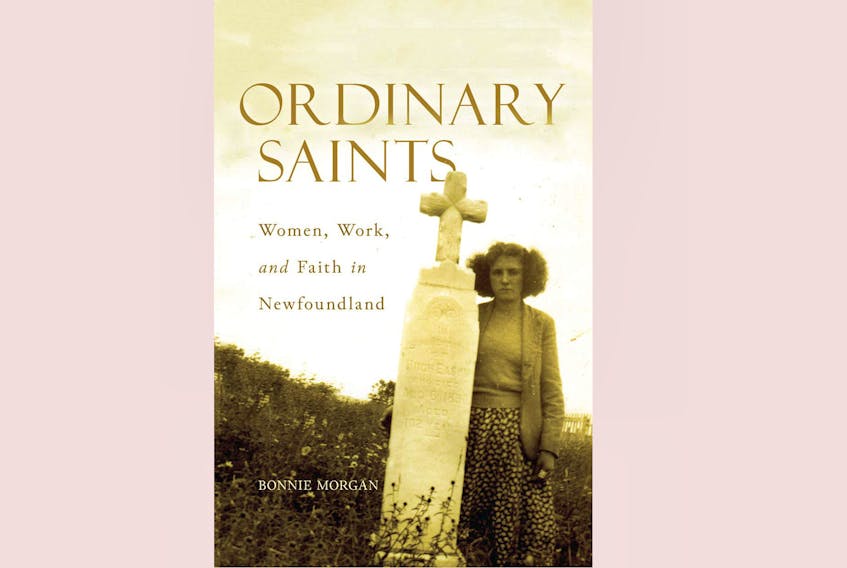

That little girl was Bonnie Morgan, and “Ordinary Saints” is her deftly researched volume (including lots of first-hand interviews), blocking out themes and arenas of women’s religious ritual, practice, and negotiation in Conception Bay. More specifically, the location is the Anglican Parish of Foxtrap and Hopewell (the communities of Seal Cove, Kelligrews, and Topsail among those enfolded), with a focus on the activities of the CEWA (Church of England Women’s Association), sieved through the author’s own connections and recollections.

The 10 chapters are “organized to establish context and to demonstrate change over time.” A throughline is women’s work and women’s roles within the spheres of home and church, how they overlapped and when they diverged.

“They Worked Harder Than the Men,” is the title of the first chapter, and certainly the household labour of childcare, cooking, and cleaning, often augmented by small-scale agricultural responsibilities, were unceasing.

Most people were poor, some very much so.

But there was some alleviation in the transition from the Depression through the Commission of Government and into Confederation. The economy opened into wage-paying jobs and social programs, meaning people had cash. Sunday observances shifted to include the enjoyably secular, such as drives in a family car, everyone clothed in their “Sunday best,” with the destination of a treat like ice cream.

Religious tasks were not restricted to Sunday, and with so much of the women’s occupation devoted to home, Morgan “explores everyday religion,” like saying grace, or nightly prayers or Bible readings. (Interestingly, Morgan also found lots of families where the father took the children to church on Sunday, freeing the mothers to focus on preparing Sunday dinner, or made the Sunday dinner themselves while their wives took the youngsters to the service.)

Then there are the ceremonies of weddings, baptisms, and funerals. At the very least significant religious touchstones in anyone’s life, but women also moved through mixed marriage (socially and ecclesiastically frowned on, but often acceptable to the families involved), childbirth and midwifery, caring for the sick, and dressing and laying out the dead (and sometimes, though this was more common to Roman Catholics, waking).

Morgan also looks at how women, or groups of women, mourned each other’s loss, and “gendered aspects of Christian consolation,” such as inscriptions on headstones.

There’s also the practice of “churching.”

Many religions have often quite long-standing prohibitions about women’s cleanliness, or lack thereof, at different times in reproductive cycles, and in this case after childbirth. New mothers were subjected to a period of time when they were not allowed to do certain tasks, like anything that got their hands wet, or dining with their family, (or touching a boat for fear of jinxing it or something like that), and were confined to home and bed until they were formally re-admitted to church.

On the one hand this gave the exhausted, post-partum woman a bit of a break. On the other we applaud the woman who pushes back at her mother-in-law’s judgment that it’s unseemly for her to join her family at dinner, stating “having a child was not a dirty thing and she was going to be eating at the table with the family.”

Women’s work under the aegis of religion also included making aprons and other textiles, and catering for church events like the opening scene of a garden party – not for nothing does she open with food, as many people can picture, if not personally remember, inviting arrays of delicious squares and pies. Sometimes recipes were also collected into cookbooks, sold as fundraisers, although such initiatives could come up against a working class versus middle class barrier, and the former’s own tradition of resisting clerical authority.

As opposed to a study of religion concentrating on male figures, priests and reverends and bishops, and male-oriented and -directed policy, “Ordinary Saints” presents the often (and often entirely) overlooked experience of the feminine and domestic – the stuff too of childhood memories. It includes tables, figures, an appendix, chapter notes, and an Index.

It’s a solid work of history, and quite readable too.

Joan Sullivan is editor of Newfoundland Quarterly magazine. She reviews both fiction and non-fiction for The Telegram.