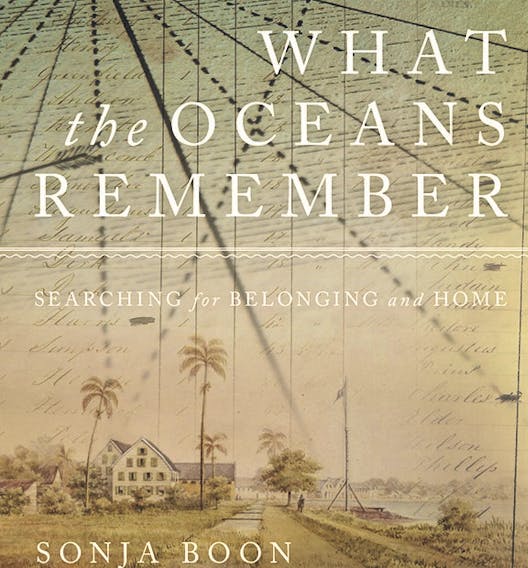

What the Oceans Remember:

Searching for Belonging and Home

By Sonja Boon

Wilfrid Laurier University Press

$29.99 336 pages

“Archives are seductive spaces,” is Sonja Boon’s enticing introduction to her layered, attentive, and nuanced exploration on legacy and self. Archives can also be intimating, emotional, intimate, inclusive, exclusive, tantalizing, and illuminating. And archives are the throughline, even the heartline, of Boon’s story here. She’s on a quest to find out who, exactly, she is.

Her family tree is complex, entwining multiple nationalities and spanning several, not just countries, but continents.

“I was born in Manchester, England, to a Dutch father and a Surinamese mother.” Boon notes. She was issued a Dutch passport; they moved to Venezuela and then immigrated to Canada where she grew up in Windsor, Ont., and rural Alberta.

In 2008. Boon interviewed for a position with Memorial University (“The search committee had booked dinner at Red Oak, a restaurant on the top floor of The Rooms. Outside, the wind and rain lashed against the windows … we couldn’t see a thing”).

She, her husband, and their two sons moved to St. John’s, capital city on an island where asking “where are you from, where do you belong?” is a cultural rite – and something Boon was increasingly inquiring of herself. Always not-quite-fitting-in, not just where she studied or visited or dwelled, but also within her own concept of herself. She’s held passports from two different countries, neither of which she was born in. And even honing answers about her origin to “Suriname” involved locating it geographically (South America’s northeast coast) and explaining it used to be called Dutch Guyana and blah, blah, blah. Exhausting. But there’s no avoiding the essential questions: “Where is home? What does it feel like, smell like? Whose voices do I hear?”

Once she marshaled herself to locate this centre, Boon a gifted and enthusiastic researcher, delved into papers and files in The Hague in The Netherlands, Paramaribo in Suriname, and the Maritime History Archive at MUN, as well as gathering copious family memories, discussions, recipes, and other lore.

Some of this was fun, and a great opportunity to reconnect with relatives. But a lot of it was deeply troubling. Because some of her family were cargo in the Dutch slave trade.

“The journal told me that it took a few months to fill a slave ship, and before it even left the coast of Africa, some of the enslaved have already died. No. 7, No. 9, and No. 2, the captain had written, his annotation embellished with a skull and crossbones. The journal recorded the next few months of the journey. Fed the slaves salt meat and fish. Saw flying fish.”

Boon has to wrestle her way through such passages, absorbing what they mean without let them overwhelm (or numb) her.

A persistent and logical mystery solver, she keeps doggedly on the trans-Atlantic trail, not deterred when a possible ancestor might simply be known by sex, age and the plantation they belonged to. When names are given, their spelling often migrates (“Johanna”; “Johana”), and, once emancipated, they might adopt new ones of their choosing.

“In some ways, archival research is a lot like music-making (Boon’s first professional training was as a professional flutist; talk about rich multiple identities!),” Boon writes. “A pianist friend of mine once told me that she saw the musical score as the point where the composer and the performer meet. The score, she said, is a place of conversation and dialogue; it’s where composer, musician, and music get to know one another … It’s much the same in the archives. I meet the past in the archives, but we need to get comfortable with one another.”

With deft and patient navigation, Boon attains this, and further, infuses the global and historic with the individual and present. The personal is historical.

There’s a wealth of data here, Boon’s curiosity lured her into ship’s logs and reparation lists, cemeteries and reading rooms, always in search of the people, her family who led to her, and to where she is now. There are also repeated evocations of nostalgia, which is not just a longing for the past but a sickness for home; as the title suggests, home is conveyed in a journey, trans-versing oceans, linking continents, carried on a wave.

The book itself is a beauty, with delicate, muted photos, map and illustrations. There are personal and enlightening chapter notes (“A story that I did not include, but which is also important to the history of slavery in Suriname, is the loss of the Leusden …”), an index and a bibliography.