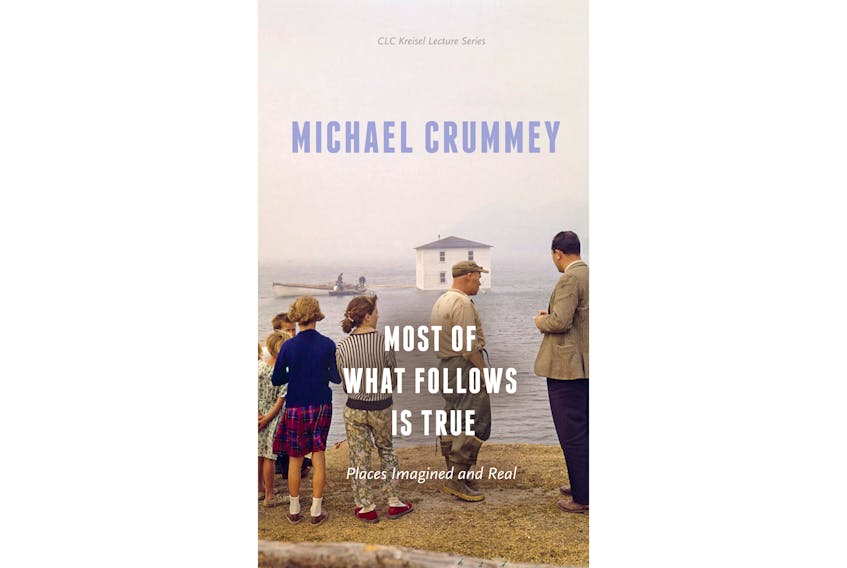

This slim volume is a transcription of Michael Crummey’s 2018 Kreisel Lecture, given at the University of Alberta’s Canadian Literature Centre. Within it, the novelist and poet grapples with the sprawling, slippery slope of truth’s relationship(s) to fiction — a task akin to trying to put a snowsuit on an octopus — lots of tentacles to tuck in, questions about who gets to tell which/whose tale, what happens to that story when you inscribe it, and what transpires when someone reads what you have written.

Crummey has published four novels (with another soon to be launched from PenguinRandomhouse) but he is most associated here with his 2001 fiction debut “River Thieves.” Indeed, he is introduced by it: Margaret Mackey, who grew up in Newfoundland, remembers how her Grade 5 history book detailed the death of Shanawdithit, dividing the time of the Beothuk into a “Before” and an “After.” She says “River Thieves” gave them a “During”; quoting Paul Chafe she adds Crummey resets this as “the fundamental loss in Newfoundland’s history — the originary moment when what could have been separated from what is.”

Though, as Crummey later explains, he never intended to write a book “’about’ the Beothuk.” For one thing, he finds books telling the Beothuk story “attempting to present these people from the inside … is completely wrongheaded.”

I’ve jumped ahead a bit here, because Crummey makes a lot of salient points before approaching this argument. He begins, entertainingly enough, with the Paul Newman/Robert Redford hit film, “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.” “A title card at the beginning of the film claims that ‘Most of what follows is true,’ which I had always taken to mean actual events determined the shape of the story, including the final scene”; also that its sepia-toned freezeframe ending “plays against type, against our expectations of the genre. … I had always assumed the film was spared a Hollywood ending by history.”

Later Crummey discovers the fate of the two outlaws was actually quite divergent from its cinematic presentation, which “made me think about that word ‘most’ at the start” (a nod in turn to this book’s title.)

Because readers, as much as film-goers, have a tendency to accept or believe what they see — especially, as most pertinent here, in historical fiction and auto(biography). Crummey decodes several ways this genre subverts, ignores, upends or ironically enhances facts. Here he largely focuses on two instances: Howard Norman and “The Bird Artist,” and Wayne Johnston and “The Colony of Unrequited Dreams,” (with lots of attentive nods to such as Lisa Moore, the much-missed Paul Bowdring, and E. Annie Proulx and her Flour Sack Coves), before returning to his own “River Thieves.”

Norman’s “The Bird Artist” (1994) sold well and was nominated for the U.S. National Book Award. Good enough. But as a story purporting to be set in a pre-First World War Newfoundland outport, it is a fiasco. Crummey’s outlining of the gaps — chasms — between what’s in the book and what would have composed the daily reality of the time is very funny, but more than a little depressing. Why set a book in Newfoundland if you can’t be bothered to check such basic facts as when Buchans was founded; what fish people caught, processed, sold and ate (do you even have to ask? Because it ain’t sea bass); or whether any fisherman’s wife took a half hour each morning to choose a dress from her ample wardrobe?

How loose a framework borders historical fiction? Johnston certainly rattled that fence with “Colony” (1998), a polarizing account of the galvanizing figure of J. R. Smallwood. Johnston’s version of the former premier pleased neither foes nor fans. He mixed real people with fictional characters, and fictionalized some actual events and details. For example, Smallwood did work as a reporter but was never at a seal hunt, and his family home was not on The Brow, where “from the front, you could see St. John’s and from the back the open Atlantic.”

To the latter point, Crummey quotes author and critic Stan Dragland’s 2001 E. J. Pratt lecture: “No assessment of any departure from fact is complete without considering whether something else is served by it.” To Dragland, Johnston’s repositioning of the house is permissible because it is symbolic, “a pivot between two great physical realities of Newfoundland,” and although neither Smallwood nor anybody really lived there “somebody ought to in a novel that dramatizes the human comedy against a huge backdrop of alien space and time.”

Which brings Crummey to his “River Thieves,” where he, like Johnston, “takes liberties with known facts in order to ‘make a story’ of past events.” He even, ingeniously, inserts his own intentions into the narrative.

This is a cogent exploration into a highly relevant topic, how fictions should, or can, or do, or must, or never will, reflect the world around us.

Joan Sullivan is editor of Newfoundland Quarterly magazine. She reviews both fiction and non-fiction for The Telegram.

RELATED: