SYDNEY, N.S. — Earthquakes and tsunamis sound like something to worry about if you live on Canada’s west coast but surprisingly, some of the worst have been experienced on this side of the country.

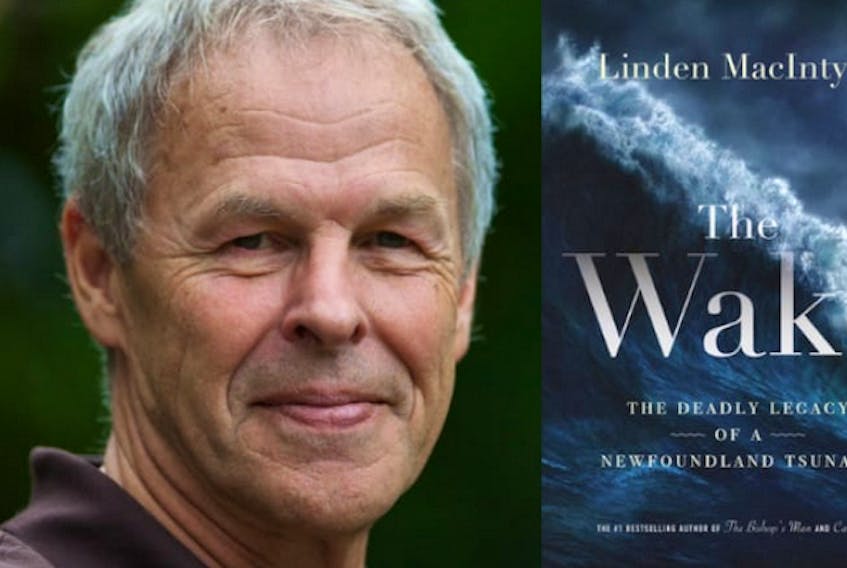

And according to “The Wake: The Deadly Legacy of a Newfoundland Tsunami,” the latest book by writer, broadcaster and investigative journalist Linden MacIntyre, the aftershocks from such an event remain long after the ground stops shaking.

One of the worst quakes in Canada’s history happened on Nov. 18, 1929, registering 7.2 on the Richter scale. The epicentre was 250 miles south of St. John’s, N.L., hitting the southern Burin Peninsula especially hard. Cape Breton and parts of Nova Scotia felt it as well, along with most of the North American east coast down to the Carolinas.

With the simplest details, MacIntyre illustrates how these major events were first noticed. In St. Lawrence, N.L., the centre of the story and where MacIntyre was born, a small boy waiting for his fried potato supper notices something odd.

“He was staring longingly at the potatoes when, to his amazement, the frying pan began to tap-dance across the stovetop.”

Tap-dancing pans were simply a prelude to the end of a way of life. Later that day, the harbour drained and a massive tsunami, caused by the quake, launched itself at the town. Twenty-eight people died and hundreds were left destitute in what was to become the beginning of St. Lawrence’s woes. After the shock of the earthquake and seeing loved ones drown, residents had to deal with yet another serious issue.

The fish were gone.

Somehow, the quake and the tsunami had destroyed the community’s fishery and as a result, their livelihoods.

“People were on their own and in a very bad state,” said MacIntyre in a recent phone conversation from Toronto.

1929 Grand Banks Earthquake

- DATE: November 18, 1929 at 5:02 p.m., Newfoundland time

- MAGNITUDE: 7.2

- AFTER EFFECTS: Tsunami followed two and a half hours later.

- DEATH TOLL: 28 in total, from the tsunami. The largest losses of life caused by an earthquake/tsunami since 1867.

- NOTE: This earthquake was felt as far as Montreal and the Carolinas and Sydney was affected by the tsunami as well although not as severely as the Burin Peninsula.

It was a prime moment for someone to step in and take advantage of the situation and inevitably, that happened. An accountant from New York managed to talk the local populace into working pretty much for free in a makeshift fluorspar mine. It was a product that would be shipped to the steel plant in Sydney.

While mining can be done safely, these were different, desperate times before health and safety regulations were in place and the watchful eye of unions. The working conditions were horrendous.

“There was no rules or regulations for any industrial activity and the mine was a pretty primitive place to work,” said MacIntyre. “Because of the fact there was no health or safety regulations people started to get sick inevitably and die. And it was discovered that the mine was a death trap.”

The men who worked the mine died routinely in their 40s and 50s and it’s here MacIntyre reveals his own history with St. Lawrence. Although he is identified as a Cape Bretoner, MacIntyre was born in St. Lawrence, the child of Cape Bretoners who moved to St. Lawrence so his father could work in the mine. Although they moved back to Cape Breton, like the others, MacIntyre’s father died when he was only 50.

“In the 1960s I became aware that something awful was happening in that little place. And what was happening was that men, miners in their 40s and 50s, were dying very badly of varying lung diseases including lung cancer. There was some publicity for a while and then it all died out.”

When MacIntyre went back to visit St. Lawrence in the 1980s, he couldn’t help but notice the local graveyard was filled with the bodies of middle-aged men who had once worked the local mines.

“My godfather had died along with his brothers — half of the men of this community — they all died from the mining diseases,” MacIntyre said, referring to the lung-related diseases like lung cancer that tend to affect miners working in unsafe conditions.

MacIntyre put the idea for a book on hold and it wasn’t until he was prodded by his editor a few years later that he returned to it. His findings were revealing.

“These people didn’t know anything about mining and there was no oversight to protect them. People died badly because of a lack of oversight and the lack of actual attention to working conditions,” he said. “The moral of the story is certainly at that time and I would argue at any time, if you have a combination of total vulnerability and an aggressive attempt to exploit people with ruthlessness, you’ll end up with tragedy. It still happens in the developing countries.”

He dedicates the book to “men and women who work hard and die slowly.”

MacIntyre, who won the Scotiabank Giller Prize for “The Bishop’s Man,” is currently working on a book of fiction.

“It’s human nature to take advantage of whatever is available in order to advance your interests. People will do it and they’ve always done if they can get away with it.”

RELATED:

Industry, media focus of Linden MacIntyre's speech to Old Sydney Society