Whenever it turns to March, and Sheila’s Brush sweeps in to wipe away the hope of spring, I always find myself thinking about the great ice fields and the men who lost their lives hunting seals.

It has been described as the worst kind of endeavour, covered in blood, and sweat and seal oil for weeks on end, with the opportunity to die in the middle. And yet they came by their hundreds for the chance. This story happened on the ice sure enough, but it was a disaster of a much different making.

It was March of 1931, and the capital city was abuzz, not just because of the herd of fearless, restless young men who had gathered to go to the ice fields hunting seals, but because the movie men were back in town.

The producers had quietly slipped into St. John’s for a private screening of their film, loosely titled, “White Thunder” or “Vikings of the Ice Field” — they had yet to decide which.

The previous March, producer Varick Frissell, backed by Paramount Pictures, and with a $100,000 budget, filmed the seal hunt along the Labrador coast, guided by the famed Arctic ice master, Capt. Bob Bartlett. Bartlett, now world famous for his trek to the North Pole with Admiral Robert Peary, even wound up with a role in the film. It was the first feature film ever to shoot sound and dialogue on location and was billed as an action adventure. The screening took place at the Nickel Theatre downtown.

But there was a problem. There just wasn’t enough action. The Paramount bigwigs decided that, at this point, they weren’t inclined to release the film.

Frissell and director George Melford decided they must grab the bull by the horns and do something about it, immediately if possible. The film needed more iceberg shots, more storm footage, more action. Soon they would get far more action than either man could handle.

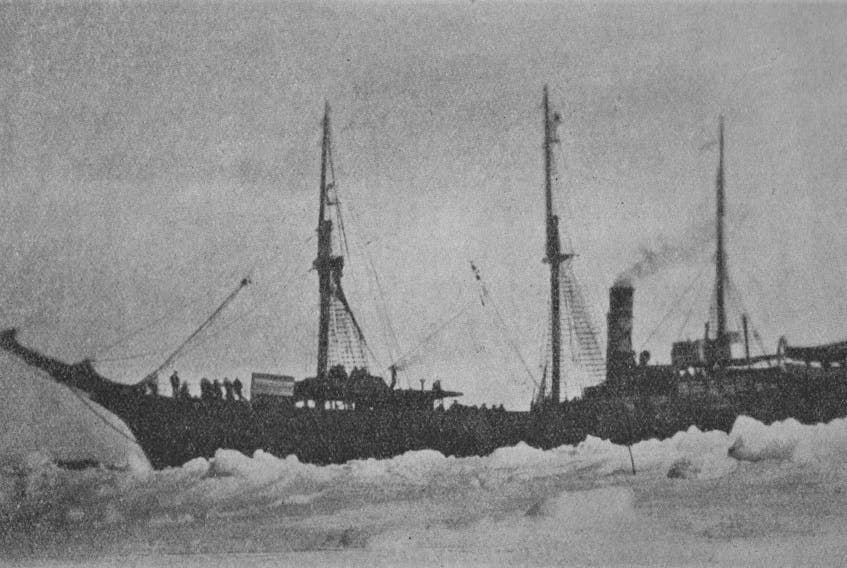

All but one ship had already left for the northern ice and the huge herds of seals. The SS Viking, a hardy Norwegian-built wooden ice ship, was about to depart with a full complement of crew and 138 sealers on board. Abram Kean, who oversaw the Newfoundland sealing disaster of 1914, was the captain. Perhaps the boys from Hollywood should have recognized the foreshadowing, but they didn’t. They quickly secured passage for themselves and their film crew, along with many boxes of “equipment,” some of which would prove deadly.

Also on board was Clayton L. King, the ship’s Marconi wireless operator from Brigus. He kept a record of the voyage and much of the information about what unfolded next was documented by him, both in “The Book of Newfoundland,” and in King’s own journal, ‘The Viking’s Last Cruise.”

It has been described as the worst kind of endeavour, covered in blood, and sweat and seal oil for weeks on end, with the opportunity to die in the middle.

“At 4 p.m., on the 9th of March 1931, the Viking, last of the northern fleet to leave port, swung her head for the channel.”

As the ship squeezed through the narrows it swung into a northeasterly gale which was bad and getting worse. For several days the heavy wooden ship pounded its way up toward Bonavista Bay. Eventually the weather broke and they prepared to set about harvesting seals.

“On Sunday, March 15th,” noted King, “at 7 p.m., when off White Bay, heavy ice was encountered, and the captain decided to stand into the ice and burn down for the night.”

This was supposed to secure the ship, holding it fast in the artic pans, while the coals were banked in the ship’s fireboxes. Kean decided to get some badly needed sleep, and left word to be called in the morning. After setting the wireless batteries to charge, King and several other fellows headed for the saloon.

King remembers seeing producer Frissell working on a piece of cardboard. “What are you doing?” He asked. “Writing out notices, Clayton, warning notices. Going to post them about the ship regarding the explosives on board,” came the reply.

Now, it was not unusual for a sealing ship to carry explosives on board, sometimes using it to break free from bad ice conditions. But the film crew had also brought their own. Film shots of ice blowing up would make for a much better movie. Frissell, according to King, was writing “NOTICE” and “DANGER” in large block letters.

“If we are not careful,” Frissell explained, ”the boys coming down the companion-way, carrying lighted cigarettes, might cause an explosion. You know, we have plenty of explosives on board.”

Then Frissell asked, almost as an afterthought, about some old flares they had stored in the captain’s stateroom.

“Better bring them out immediately,” he said. “They’re a serious menace, if kept there.”

The boatswain, a man named Carter, retrieved them, then upon his return asked for a cigarette, which he took, but did not light.

“Carter,” said Frissell, “those flares are damaged, and are not safe to keep aboard. Better take them out and throw them over the side.”

“I’ll keep them and make some experiments on the ice tomorrow,” said Carter. “Don’t you dare!” came the reply. “If you fool with them, we’ll all be blown to Hades before daylight.”

Carter picked up the flares and left. Shortly after the ship lurched terribly, and then a massive explosion occurred.

Whether Carter’s departure with the damaged flares and the cigarette had anything to do with the massive explosion, we will never know, but now the ship and its crew was in grave danger. Some were already dead. There was an eerie silence, followed by, as King put it, “a terrific, roaring, blooming blast.”

King regained consciousness on the saloon deck, and realized he had to get out, or be burned to death. He somehow managed to push a piece of timber off his legs. As he struggled to get out, he saw someone running to the back of the ship, a living torch of flame.

“My legs were terribly broken up. I thought I heard running water. It was blood, running down the side of my head and across my ear.”

He thought of his mother and father. The flames were at him now. His clothing was on fire, his hair burning. He prayed for strength and pulled himself along the deck and out of the inferno. His hair came out by the handfuls. He managed to beat out the flames. “The will to live is great. Life is sweet, even at it’s worst,” he wrote.

But it was far from over. Explosions continued to wreck the ship. The navigator, a Capt. William Kennedy, called to him from the ice. He was standing in a pool of blood, and begging King to come get him, not realizing how badly hurt King was himself. It took everything King had to somehow drag his own body over the side and into the icy North Atlantic. But he could not get a grip on the ice pans, which were “slippery and hard as steel,” and he was struggling in the frigid water.

Another man named Harry Sargent came to his aid. He dragged him up on the ice. Together the three men somehow managed to get clear of the ship and cling to a piece of wooden wreckage on an ice pan. The ice was littered with chunks of wood, pieces of sail and equipment of every description. From a distance they sat watching the SS Viking burning, as shadowy figures in the dark either jumped or fell from the doomed ship.

They were drifting now, away from the burning ship, and soon realized a horrible irony. “It was a cold winter’s night, and regardless of all the fire (we had already) gone through, it was now necessary to build a small one in order to live. Running from one fire to save our lives and now having to build one for the same reason.”

The three men huddled on a piece of wreckage and concluded two things: the other survivors must have struck out for shore, likely the nearby Horse Islands, just north of Fleur de Lys, and secondly, that their ship was about to meet its end. They watched in silence as, in the distance, the fiery SS Viking went to its Valhalla, and slipped to the bottom of the North Atlantic.

Days passed. King slipped in and out of consciousness. Unknown to the three, the fire had been seen from Horse Islands and a search was underway. A special message from the radio operator at Horse Islands had been sent by operator Otis Bartlett to The Evening Telegram at 10 a.m. the next morning: “118 landed here safe many suffering severe injuries. Six men left here to search for operator.”

“The operator” was a reference to King. The rescue ship Sagona eventually spotted the men and got them aboard. It was amazing that King was alive at all. Both his legs were badly twisted and shattered. Only the fact that they were both frozen made him able to stand the pain. One eye was badly injured, and he had severe burns. Kennedy survived to get on board but died just a few hours before the ship reached St. John’s. It was said that Sargent, King’s saviour, was able to walk off the ship on his own.

It would take several operations and a lot of luck for Clayton King to see home again. Both legs had to be amputated. Some sort of shrapnel, a projectile from the explosion, was found buried deep inside his head. And there were the burns.

In all, 28 men lost their lives that day, including producer Varick Frissell. But, as the saying goes, “the show must go on.”

The film, renamed “The Viking,” was released in June of 1931, and was generally panned by the critics, some of whom found the dialogue and story line to be “sketchy.”

A government commission later could not really find any definitive cause of the tragedy other than that the explosives magazine had done exactly that — exploded. The incident itself remains at the top of the list in terms of movie films in which people were killed during the production.

Clayton L. King recovered, a much-changed man, and returned to Brigus. To the end of his days, I have no doubt, March weather and talk of sealing always made him think about “that time I almost died, out on the ice.”

Reg Sherren is a writer whose book, “That Wasn’t the Plan,” is scheduled for release this fall.