ST. JOHN'S, N.L. — Tara Bradbury

The Telegram

@tara_bradbury

A Botwood man convicted in 2017 of sexually abusing a child more than 40 years ago has won his appeal, with two of three appeal judges agreeing the jury did not have enough evidence to find him guilty.

A jury found Angus Waterman guilty in November 2017 of multiple crimes related to the sexual abuse of a child between 1974 and 1981. Waterman was sentenced to a year behind bars.

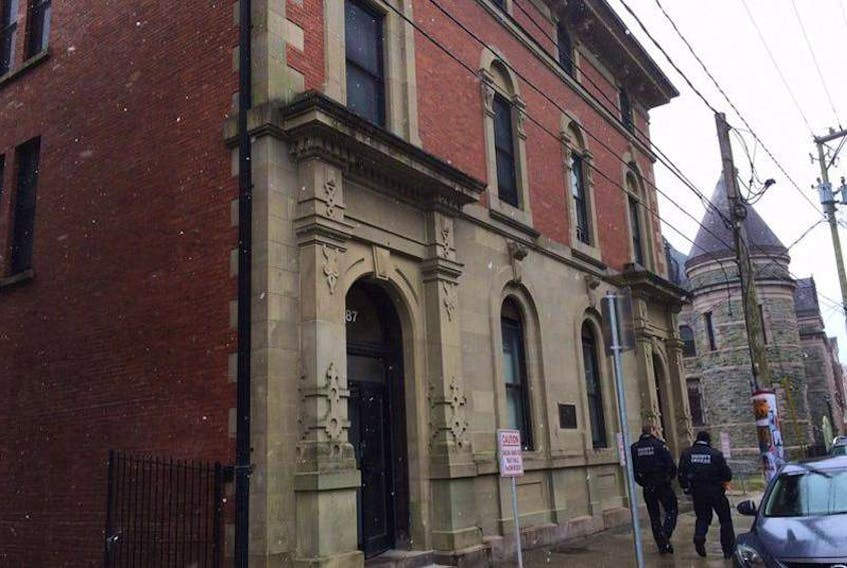

Waterman’s appeal was heard last year — long after his time had been served. This week the Newfoundland and Labrador Court of Appeal released its decision to acquit him of the charges, with one of the three judges dissenting.

The complainant had been living in another province when he reported the alleged abuse to police in 2015, triggered, he said, by a video he had seen on social media of a robbery involving Waterman’s son.

At trial, the complainant told the court about five instances of sexual assault he alleged Waterman had committed on him when he was a child. Some details of his testimony were significantly different from what he had told police and what he had testified at the preliminary inquiry, including some of the locations, circumstances and actions involved.

When questioned, the man said the details he had given police were what he had remembered at the time, prior to undergoing counselling, and he had been having trouble separating constant nightmares from reality. He described being “all over the place” when it came to his memories and said it had taken counselling to get them “all pieced together like a puzzle.”

The issue of recovered memories is not unfamiliar to the courts, especially in cases of sexual abuse and other trauma. Dissociative amnesia is a disorder that includes, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5, “the inability to recall important autobiographical information that should be successfully stored in memory and ordinarily would be readily remembered.” The amnesia is often associated with childhood trauma.

The concept of repressed and recovered memories is a controversial one in psychological circles, and some believe certain therapies can result in patients remembering things that didn’t actually occur.

In Waterman’s case, the trial judge instructed the jury to consider the discrepancies in testimony during their deliberations. They found Waterman guilty nonetheless.

Waterman’s lawyer, Randy Piercey, argued on appeal that the jury did not have enough evidence to reach that verdict, relying on testimony.

Ruling on the appeal, Justice Gale Welsh and Justice Charles White agreed.

The complainant’s counselling sessions and their effect on his memories was an important one, Welsh wrote, and the circumstances called for an expert to give evidence.

“However, the Crown, which had the onus of proving the offences beyond a reasonable doubt, did not adduce expert evidence to assist the jury in assessing the possible effect of counselling in the complainant’s explanation for the numerous and substantial changes in his story.

“Given the nature and extent of the inconsistencies in this case, and the manner in which the complaint recovered the memory by relying on counselling, it cannot be said that the jury had the necessary tools to reasonably resolve such doubt as may have been created by the inconsistencies. This amounted to a failure by the Crown to provide the necessary evidentiary basis for a conviction.”

White said some of the complainant’s inconsistencies were minor and understandable, but put together with other more significant ones — including telling police that Waterman had committed certain actions, but later testifying Waterman had threatened them, not committed them — there was enough to question whether the Crown had proven its case.

“In my view, the complainant’s evidence was of such a nature that it was unsafe to rely on it as the basis for a conviction,” White wrote.

Justice Gillian Butler disagreed, cautioning the other judges against playing the role of “13th juror” and suggesting it would be “dangerous” to conclude that an expert opinion was needed in order to believe the complainant.

Butler pointed out there were numerous consistent and unwavering details in the complainant’s testimony related to acts of sexual assault. She noted there had been inconsistencies in Waterman’s evidence, too, and discrepancies between his testimony and that of his wife.

“The identified inconsistencies do not go to the core evidence which established the elements of the offences,” Butler said. “The jury decided after considering the evidence as a whole that it believed the complainant’s core evidence. It was open to the jury to conclude that, as between the complainant on one hand and the appellant and his wife on the other, they believed the complainant.”