A Dalhousie University researcher has found that the oceans have gotten a bit more quiet during the time of COVID-19.

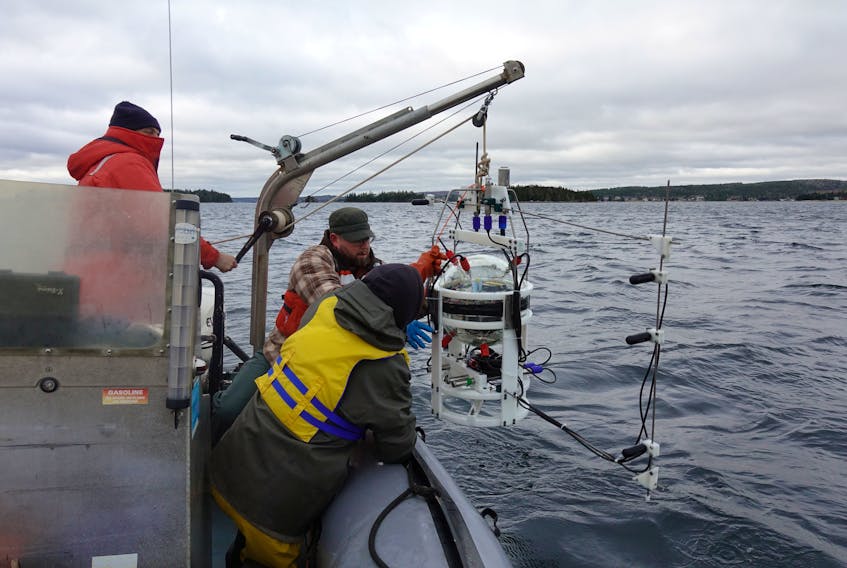

David Barclay, assistant professor in Dal's Department of Oceanography, turned to underwater microphones – hydrophones – deployed off the coast of British Columbia to check on noise levels in the Pacific.

Barclay said he chose the waters on the opposite coast because Ocean Network Canada's VENUS observatory, short for Victoria Experimental Network Under the Sea, and the North East Pacific Time-series Underwater Networked Experiments (NEWTUNE) observatory, are attached via cables to servers to collect data in real time.

VENUS is in the inland waters of the Salish Sea, Strait of Georgia, and Juan de Fuca Strait. NEPTUNE goes off the continental shelf, about 300 kilometres offshore and about 3,000 metres deep, he said.

“And so, the neat thing about it is, typically, in my line of work, you have your recorder, you go out on a boat, you put it in the water, you go home, you come back a month later or a year later, or whenever, then you collect it and then you analyze all the data. But in this case, the real neat thing was we could, from Halifax – from home, even – could just go online and actually download data from five minutes ago. We could download the most recent data.”

Ocean acoustics affected by large vessel

Natural ocean sound

It's accessible to the public, free of charge, with no barriers to that data, Barclay said.

The hydrophones have been in place for years, so they also had access to historical data for comparisons.

Barclay said he worked with Air Force Maj. Dugald Thomson, a Ph.D. student in his lab who is currently posted in Victoria.

The hypothesis they were testing related to how the underwater noise related to shipping traffic has been reduced by COVID-19 mitigation measures.

“We haven't actually looked too much into the detail of how the actual traffic has slowed down,” Barclay said. “But we had this one statistic that was pretty juicy, which was that the dollar value of imports and exports out of the port of Vancouver had decreased by 20 per cent. So we thought either there's less ships or there's ships carrying less things, so lighter ships which are potentially less noisy or ... a number of factors that could be there.”

"The real neat thing was we could, from Halifax – from home, even – could just go online and actually download data (off British Columbia) from five minutes ago. We could download the most recent data."

- David Barclay, Dalhousie Department of Oceanography

They decided to compare the noise levels over the time period from January to March to historical records for the same time period in other years.

“We found two different results because of these two different environments.”

Barclay said the offshore, deep-water environment allows sound to propagate very efficiently and very far – thousands of kilometres. Sound travels better there than in the relatively shallow inshore waters.

“It's sort of like being in a cathedral as opposed to being in a quiet office,” he said.

They looked at noise produced at a frequency of 100 Hz, a relatively low frequency that is associated mostly with noise produced by engines and propellers.

In the deep Pacific, they saw a 1.5-decibel decrease in weekly noise power, which is statistically significant, relative to last year. In the inshore waters, the reduction was an average of about 5 decibels, or almost 50 per cent of 2019 levels.

“The reasons for (the decrease) being larger in inland waters, and that's right outside the port of Vancouver, is because there the main noise you're dealing with is the ships coming right next to you, driving right overhead.”

Their research paper has been published in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America.

The implications on ocean life implication could be wide-reaching, he said.

Past research by Susan Parks on North Atlantic right whales in the Bay of Fundy has shown stress levels dropped when shipping was reduced due to the 9-11 attacks, Barclay said.

He said he can't do similar research on the East Coast at this time because the hydrophones deployed in the Atlantic are not cabled to allow the transmission of data in real time, but he lauded the efforts of the International Quiet Ocean Experiment to co-ordinate research around the world.

“And I certainly do know that there are a couple of excellent scientists at DFO that are collecting the data, so we will get that answer, we just don't have the nice bells and whistles that they have on the West Coast to get it now. We're going to have to wait a little bit.”