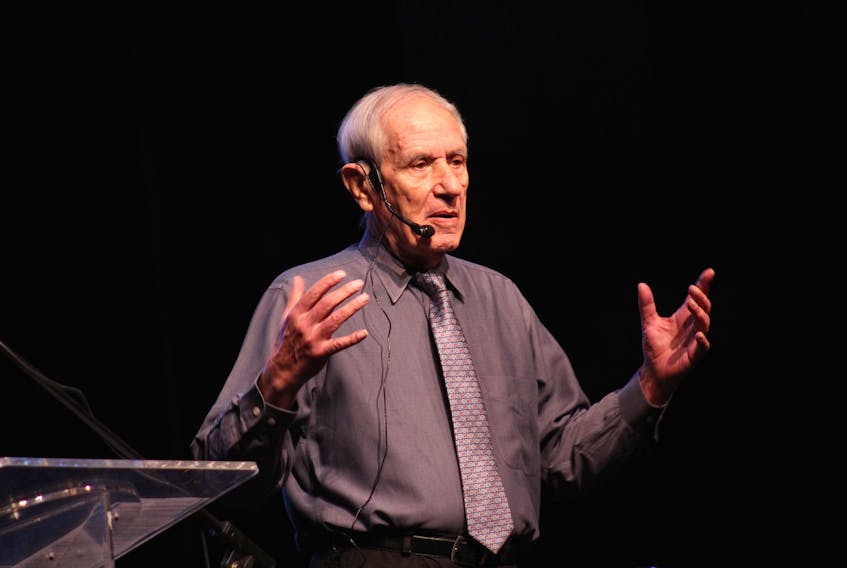

Douglas Cardinal told Indigenous students that nothing is impossible if they believe the teachings of their ancestors.

“My elders always taught me that we are magical beings clothed in flesh,” said the renowned Indigenous architect.

“We have all the power we need to fulfill our vision, that’s the greatest and most beautiful knowledge you can have from our elders.”

The Anishinaabe elder spoke Friday to a group of more than 300 students gathered at the Membertou Trade and Convention Centre in an address by organizer Digital Mi’kmaq, a grassroots initiative that aims to create lasting opportunities for Indigenous youth and communities.

Born in Calgary, Alta., Cardinal is credited with creating an Indigenous style of Canadian architecture that is characterized by organic forms that challenged the most advanced engineering standards.

For his early days, Cardinal said he grew up in a cabin with no running water or electricity and was taught by his father to live off the land.

“He always wanted me to have an education,” said Cardinal. “He said ‘You could be whatever you want to be.’”

But it was Cardinal’s mother who planted the seed of him becoming an architect as she welcomed the idea of him creating beautiful spaces.

Accomplished at drawing, Cardinal would travel to the United States to study architecture at the University of Texas in Austin.

“I owe a lot to Texas for giving me a good education,” he said.

“They were doing things in a very traditional way. They didn’t even have the technology to have drafting machines, they used parallel bars, and so, I was always thinking about the latest tools even then when I first started.”

Among the profession’s early struggles was having to draw everything by hand using ink and linen. Cardinal said this always seemed to him like an arduous task.

By as early as the 1960’s, Cardinal and his team began using computers to calculate complex organic forms, most notably in the curved roof of his first masterpiece, St. Mary's Church in Red Deer, Alta.

“They said it would take seven men 100 years just to work out all the calculations, so it was impossible,” said Cardinal. “I was always told by my father that nothing is impossible. We declared very strongly that we were going to do it no matter what. And when you make a declaration that you’re going to do something there’s a lot of power in that.”

Cardinal would later find a computer in Chicago that allowed them to solve their calculations in a matter of days.

He incorporated the technology further to increase the dimensioning precision and affordability of his organic forms, and by the late 1970s had become the first architectural practice to be entirely computerized, utilizing an architectural program designed exclusively for his firm.

Cardinal said he designs his buildings around their function and uses topography to start shaping the space from the outside in.

In 1983, he was summoned by Pierre Trudeau, the then prime minister of Canada to begin work on a new national museum now known as the Canadian Museum of History.

“He didn’t want it to be from the culture of England or the culture of France, he wanted it to come from the land and so he really supported this very organic approach to architecture,” said Cardinal.

“You are shaped by your environment, so what kind of environment do you want to shape the future? And so, it’s a real responsibility to be an architect because you’re shaping the way that people think and feel.”

After working long days for seven years on its architecture, Cardinal welcomed the opening of the museum in 1989.

He would return to the space a few years ago to incorporate an Indigenous footprint into a problematic history hall that began only with first contact from European settlers.

“Each one of you have a gift right here, all the power that you need is really right here within yourself,” Cardinal told the students.

“When you connect to the source, to the creator, then you become a sorcerer. A magical being. You have the power to do anything that you can imagine. That’s your gift.”

Now in his 80s, Cardinal continues to work including the development of a world collaborative centre his firm is designing for Cape Breton University.