As cases of the coronavirus (COVID-19 strain) continue to grow on P.E.I., one Island historian reminds Islanders that it isn't the first time the province has gone to war with an invisible enemy.

In October 1918, the Spanish influenza infected hundreds of people in a matter of days.

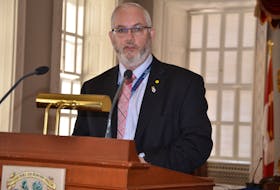

"Canada had just lost 66,000 to the Great War and would continue to lose people. Then the Spanish influenza strikes and we lose an estimated 50,000 more to the pandemic," said Matthew McRae, curator of history with P.E.I. Museum and Heritage Museum.

What many might not know, he said, was there were two waves to the influenza pandemic.

"The first wave wasn't as fatal. But sometime over the summer, for reasons I don't know, the disease mutated and it became deadly."

The Island's possible patient zero was Mary Herrell who fell ill with the flu while coming home from a vacation in Boston, bringing the virus back with her to Charlottetown. According to the book, If You're Stronghearted Prince Edward Island in the Twentieth Century, by Ed MacDonald, after an eight-day illness, Herrell died on Oct. 2.

By Oct. 12, over 600 cases had been reported in the province's capital.

"Charlottetown became the epicentre for the flu outbreak on the Island. Funerals were cancelled, bodies of people who died by the flu or, in most cases, pneumonia as a result of the flu were buried within 24 hours."

Like the current coronavirus pandemic, the provincial chief health officer closed schools, cancelled church services and banned all public gatherings.

During the 1918-1919 Island epidemic, media outlets close to home like The Guardian were skeptical of the virus.

"The local press was very dismissive. I don't know why. Maybe they genuinely believed it wasn't serious and it would be gone or it would take away from the victory of the war," said McRae.

SPREADS TO COUNTRY

By November, restrictions in the province's capital were lifted, but the virus had begun to spread to Island countrysides.

"It didn't kill the ones you'd typically see impacted by an epidemic, it killed the young and the healthy and awful stories followed where the virus went," he added.

In Central Bedeque, Mary Webster's great-grandmother, Anna Webster (nee Ellis), was 41 and pregnant with her seventh child when she contracted the flu.

"Mother passed away March 13th 1919. She had Spanish influenza that the soldiers brought back from overseas. (It) was a terrible epidemic. She was 41," said Webster, reading off the back of an old photo of her great-grandmother.

She survived the first wave but died during the second, Webster said.

"According to her late daughter, 'all of the pregnant ones did'. The Spanish flu targetted people in their 20s and 30s in the prime of their lives, as well as the immunocompromised people, like pregnant women. Deaths like this devastated family units and meant that children (in the case of the Websters, the tween-aged daughters) suddenly had to mother younger siblings and take charge of the house."

McRae agreed.

"It changed people's behaviour, lives, the economy went into a free fall. Some of this might sound familiar to today's COVID-19 outbreak."

"One story (Ed MacDonald) detailed in his book was of a household that boarded up the first floor of their house and (they) stayed on the second floor. Wakes for the family were held in a field because people were terrified to go into the house for fear they might contract the virus."

Another story told of a wife who had died while her husband was off to war. By his return, his two children had been moved to an orphanage.

Eventually, life returned to normal in the 1920s, said McRae.

What's in a name?

- Did you know the Spanish flu didn't originate in Spain? During the time of the pandemic, several countries were in the grip of the First World War. Allied countries wanted to keep morale up on the homefront, resulting in governments and news outlets preventing the spread of serious news that could take away from the war.

- Specfically, the United States had the Sedition Act, which prevented individuals from saying negative things about the country.

- Because of these boundaries, reports of the Spanish influenza were not shared in the news. However, Spain was neutral during the war and had more open reporting in the news. As Spanish outlets covered the influenza virus, other countries were just hearing about it, leaving people to think it came from Spain.

- In actuality, there is speculation that the epicentre of the North American outbreak could have been at a military base in Boston or in Kansas.

SMALLPOX ARRIVES

The Spanish Influenza outbreak wasn't the first disease to come to P.E.I.

In late 1885, the Canadian smallpox epidemic reached the Island.

Like COVID-19 and the Spanish flu, the smallpox outbreak was caused by a virus.

"It had been around for at least 2,000 years. It was something people were really afraid of," said McRae.

While working in Winnipeg, Man., several years ago, McRae was researching smallpox.

"I would look through a lot of diaries and journals, but in November 1885, people were talking about the Louis Riel hanging, the national park opening and generally smallpox."

It's believed smallpox came to the Island after a ship from Montreal docked in the Charlottetown harbour, said McRae. Although a vaccine was available for the virus then, the resource was inadequate on P.E.I.

"By Nov. 12, the virus had been found on the Island and soon it spread through Charlottetown. As more and more people caught the virus, areas were fumigated."

The Charlottetown Patriot had staffers vaccinated for the disease and had newspapers fumigated before delivery.

"It was this outbreak that made vaccinations compulsory for adults and children. No one could teach in schools unless they could prove they were vaccinated."

The epidemic drew attention from the anti-vaccination movement.

"For smallpox, the process of inoculating someone against the virus was taking someone who had a weak infection and having them scratch the skin of someone without it."

Symptoms of the Spanish flu

- Bleeding from mucous membranes (eyes, ears, nose, mouth, vagina)

- Tremours

- Hemoragged internal organs

- Dried brain tissue

- Turning blue due to hypoxia

- Extreme pain, aches, chills and fever

- Lung damage that looked like it could have been caused by toxic gas or pneumonic plague

SOURCE: This Podcast Will Kill You Episode 1: Influenza will Kill You

HISTORY REMEMBERED

While the diseases had a role to play in Canadian history, McRae said the Spanish flu is looked at as a footnote.

"It's all very contained in the oral histories of families. We were coming on the tail end of World War One, and that overshadowed it to some extent."

He added, "But with that, it reminds Islanders that we have been faced with this (COVID-19 like events) before and we have come out on the other side.

"It's a story about survival and it's reassuring that life will go on."