Canada’s prison watchdog is raising alarms about the use of force at New Brunswick's Atlantic Institution, the only maximum-security federal prison in the region.

The annual report, tabled Tuesday, looked at problems in Canada’s prison system through three case studies. One examined the use of force at the prison in Renous.

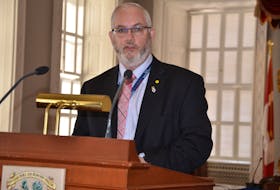

The report outlines what correctional investigator Ivan Zinger calls an “entrenched staff culture and attitude” that gives license to a security-first response approach and trumps other ways of dealing with conflict and non-compliant behaviour.

To conduct the review, Zinger’s office completed a comprehensive review of 310 use-of-force incidents that occurred at the 330-capacity Atlantic Institution over a four-year period, with incident dates ranging from July 2014 to February 2019

Zinger said in his report that his review found recurring patterns of non-compliance with use of force policy and procedure and this culture remains “largely impervious to change” despite repeated interventions by his office, leaving him no choice but to elevate the issue nationally. Some of these troubling examples of non-compliance included incomplete incident reports that left out events that occurred during a use-of-force incident, handheld cameras not being consistently used by staff when force was likely to be used, and significant delays in providing decontamination showers following deployment of inflammatory agents like pepper spray — in some cases as long as 12 hours.

Although for the four-year period encompassed by the review, the annual number of uses of force fluctuated from a low of 52 to a high of 81 — comparable to other maximum-security institutions — Zinger’s report said In 2017-18 alone, Atlantic Institution used 257 types of force in 73 incidents, translating into a ratio of 3.5 uses of force per incident. That was the highest ratio for any institution over the four-year period from 2014-15 to 2018-19.

The review also found that force was still being used on individuals who had become compliant during the incident despite the law instructing that use of force responses are supposed to be "necessary and proportionate."

Zinger’s report also raised concern about another alarming trend: the over-reliance of pepper spray to gain control over inmates.

“Not only was the use of pepper spray high at Atlantic Institution, it seems to be the tool of choice to deal with non-compliant behaviour,” the report reads.

Moreover, responding officers often resorted to using a delivery method called ISPRA to deploy inflammatory agents, which is a much more powerful delivery mechanism than pepper spray canisters worn on an officer's duty belt.

In 2017-18, Atlantic institution recorded 167 uses of pepper spray in 73 separate use of force incidents, which was the highest recorded use of pepper spray of all maximum-security institutions. Atlantic Institution also had the highest use of the ISPRA in 2017-18 at 113 uses compared to the next highest institution, Edmonton, with just five uses.

Use of force indicator of larger issue

For advocates like El Jones, a sociology instructor at Mount Saint Vincent University and Saint Mary’s University, and board member for East Coast Prison Justice, the report doesn’t come as a surprise.

Jones said these use of force incidents are a symptom of a large issue of declining rights of prisoners in Canada.

She said whenever there are reports of use of force or institutional violence that should always be seen as a red flag for what's happening at the institution in general, not as a sign of inmate behaviour but as a sign of conditions in the facility.

“We sort of see a cycling of conditions in these high-security institutions where there's just a constant crackdown,” she said,

“It becomes normal to not be out of your cell it becomes normal to have programs cancelled, it becomes normal to not have visits and that then creates a hostile environment it creates a stressful environment, (...) and that leads to violence and the removal of more rights.”

Senator Kim Pate, former executive director of the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies says the level of violent incidents in prisons, particularly maximums security is part of the reason why she has been advocating for more oversight in the prison system, especially with regards to amendments to the Liberal’s solitary confinement reform bill that passed last year. Her amendments, which were rejected, would require the Correctional Service of Canada to apply to a superior court to keep a prisoner in isolation for more than 48 hours. Solitary confinement has been known to cause a host of detrimental psychological effects, which can lead to violence, and in some cases has been declared to violate charter rights.

“Even though [the Correctional Service of Canada] claims they've eliminated the use of segregation [...] they [have] just renamed segregation. In most of the prisons, including particularly the maximum-security prisons, they have become more and more like segregation units because people are often locked in those units for extended periods of time, often even further cell confined during lockdowns.”

Pate said Senate studies have also noted reduced access to programs and services and more limited access to loved ones.

“If you want to increase the likelihood of people integrating safely into the community after prison, then a little strong community of support is vital,” she said.

Jones said it is difficult to amass any political will to make the changes needed in prisons as the public tends to have little sympathy for the incarcerated. But, she said, advocates aren't calling for gold plated cells, they’re calling for programming, education, community integration, mental health support, and basic and health and safety interventions -- all of which, she said, are proven to make jails safer for prisoners and staff.

“It's very easy to picture them and say these are all murderers and rapists but it’s poor people, its traumatized people, its vulnerable people [...] it’s society’s mentally ill, its Indigenous people, it’s black people, it’s people with disabilities, and they should not be discarded,” she said. “They deserve human rights.”

In order to address the issues outlined in Zinger’s report, he recommends that CSC establish a working group with external representation, to complete a review of all use of force incidents over a two-year period at maximum-security facilities. The review, he said, should go beyond compliance issues to include a look at trends and culture, best practices from around the world, and an action plan that includes retraining, disciplinary action, and mentoring.

Anne Kelly, the Commissioner of the Correctional Service of Canada, issued the following statement following Zinger’s report saying she welcomed the findings.

“CSC has carefully reviewed all recommendations put forward by the [investigator] and work has been ongoing within CSC to address them,” she said.