ST. JOHN'S, N.L. — First it was shock. Then disbelief.

Then, Jenny Wright says, her feelings upon hearing of a mistrial in the case of RNC Const. Doug Snelgrove Friday turned to anger at a justice system she believes needs an overhaul, especially when it comes to the treatment of women reporting sexual violence.

“This trial is just a classic example of how our justice system is broken and continues to harm and re-harm and traumatize (those reporting sexual violence),” said Wright, women’s rights activist and counsellor.

Snelgrove, charged with sexually assaulting a woman while on duty in St. John’s in 2014, has gone to trial on the charge twice. Each time, the verdict was affected by a mistake on the part of the judge.

Snelgrove was acquitted by a jury in 2017 before the Crown appealed and a new trial was ordered. The province’s Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court of Canada agreed the original trial judge had erred in her instructions to the jury by not explaining to them a part of the law pertaining to consent — specifically, that a person cannot legally give consent to sexual activity to someone in a position of power, trust or authority if that someone abused their position to induce it.

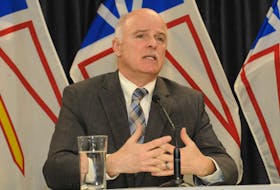

That was an area of the law Newfoundland and Labrador Supreme Court Justice Garrett Handrigan, who presided over Snelgrove’s second trial, had presented in detail and at length during his final instructions to the jury Thursday.

“Let me put that in the context of this case for you,” he told the jurors, before sequestering them to begin their verdict deliberations. “If you find that (the complainant) consented to the sexual activity that occurred between her and Mr. Snelgrove, you must find there was no consent if Mr. Snelgrove induced her to engage in the sexual activity by abusing any position of authority in which he stood towards her.”

Handrigan said the jurors should take it as a given that Snelgrove was in a position of authority over the woman, given he was on duty in a police uniform and a marked police vehicle.

After about 90 minutes, the jury returned to the courtroom to request permission to review the audio recording of a witness's testimony. At that time, Handrigan informed them he had realized he made a mistake earlier in the day when he dismissed two alternate jurors.

Since there had been issues with the jury selection at the start of the trial — when a number of jurors had asked to be excused, forcing sheriffs to take to the streets to find replacements for them — Handrigan had opted to keep 12 jurors and two alternate jurors in the jury box throughout the proceedings. Just before sequestering them to begin their deliberations, he dismissed the two alternates, telling jurors No. 13 and No. 14 they were free to leave.

The usual procedure is for the court to draw two jurors’ numbers randomly.

The judge adjourned the deliberations for the rest of the day, advising defence lawyers Randy Piercey and Jon Noonan and Crown prosecutor Lloyd Strickland to take the evening to decide whether they wanted to declare a mistrial as a result of his mistake or carry on. Proceeding despite the mistake would mean waiving the right to appeal on the basis of the error if the jury were to find Snelgrove guilty.

When court resumed Friday morning, the defence argued for a mistrial, while the Crown argued for the matter to proceed. After a 20-minute recess, Handrigan declared a mistrial and called the jury in to inform and dismiss them.

“Essentially, you are not a properly constituted jury,” Handrigan told them. “I’ve considered possible remedies and I can’t find one that’s suitable in the circumstances at this time.”

Handrigan said he had considered Strickland’s suggestion of calling back the two dismissed alternate jurors, then drawing numbers, but concluded it wasn’t appropriate, since they had already been away from the jury overnight.

“In the circumstances, I don’t think I could possibly undo any damage that might have been done to ensure that you are properly constituted to come to a verdict,” Handrigan told the jury.

He thanked the jurors and told them he was sorry.

Piercey and Noonan took issue with the Crown’s characterization of the judge’s mistake as a technicality, calling it a fatal error instead. They said in an emailed statement a mistrial was unavoidable in the circumstance.

“We didn’t ask for a mistrial so much as we acknowledged to the court that the error meant the jury was improperly constituted and a mistrial was the only available remedy,” Piercey and Noonan said.

Snelgrove had been anxious to resolve the matter, the lawyers said, and they came prepared for the trial.

“We were satisfied with the case we presented and the jury that was selected,” they said. “This was unfortunate for all stakeholders and certainly was not the intent of any party involved, including the court.”

Strickland, who had presented prior legal decisions to support his argument that the error wouldn’t affect the fairness of the proceedings, spoke to reporters outside the courtroom. He said he was disappointed for the court and the participants, particularly the complainant. She has now testified twice and would be expected to testify again if a third trial happens, unless Crown and defence lawyers agree to present her evidence instead through a written statement of facts.

“We will weigh everything, but it is our intention, all things being equal, to proceed with the retrial,” Strickland told reporters.

The complainant’s wishes will be an important consideration, he said.

Snelgrove, who left the building through a side door once the mistrial was declared, is set to be arraigned again in St. John’s Oct. 5.

Public outrage to the mistrial declaration was swift and much of it was similar to that expressed by Wright. Many people offered messages of support to the complainant, whose identity is protected by a publication ban.

A small group of women took to the steps outside the Newfoundland and Labrador Supreme Court courthouse in St John’s Saturday morning to express their outrage over the mistrial, carrying signs with phrases like “He had a gun,” and “Seriously?”

Response on social media echoed the same outrage, with many calling the mistrial a travesty.

“Our collective anger is overflowing. Two trials, two judges, two mistakes = no justice. Again and again and again,” wrote one woman.

The effects of the court process on a complainant are wide-ranging, Wright said, and include mental-health and financial impacts.

The public effects of the situation will also be multi-levelled, she said, especially given the serious nature of the allegation against Snelgrove and the fact he was a uniformed officer on duty with a weapon.

The Newfoundland and Labrador Sexual Assault Crisis and Prevention Centre also issued a statement Friday, saying it was “overwhelmed with grief, with anger, with disbelief."

“Without change, our systems will continue to retraumatize survivors,” the centre wrote, offering a message of support to those who have experienced sexual violence.

“Trauma has ripple effects — for individuals and for communities. Our community will continue to feel the impacts of these traumas for a long time.”

The centre offered its 24-hour, seven-day-a-week confidential support line: 1-800-726-2743. It can also be found online at www.endsexualviolence.com.