ST. JOHN'S, N.L. — Andrew Waterman

The Telegram

Over a 25-year career as an architectural photographer, Richard Johnson has taken photos of a lot of different buildings and rooms, but what fascinates him the most are small, man-made structures.

Johnson, who is based in Toronto, took an interest in root cellars — structures built in the side of small hills or underground, once commonly used to store vegetables — when he was in Newfoundland and Labrador taking photos of ice huts for a series.

“It took me 10 years to capture all the ice fishing huts from coast to coast,” Johnson said. “The root cellars of Newfoundland caught my eye back in 2012.”

Being that it was winter, the root cellars he saw were buried, so he stored what would become his latest project until 2018, when he came back to the island on a three-week visit to photograph the cold, dark and dry cellars, once necessary to get families through the winter.

“With the root cellars, I had to get into people’s backyards and onto private property, so for me it meant having to knock on doors and talk to people and engage in a way that was out of my comfort zone,” Johnson said. “It was a wonderful, extra level of interaction this project brought to me, because I was meeting all these people.”

He was drawn to root cellars because of their simplicity, he says.

“You don’t need electricity and intervention from mechanical systems, it’s just designed correctly,” he said. “That’s the beauty of it, it’s so simple.”

Fixture of surroundings

Root cellars were a fixture of Marilyn Coles-Hayley's surroundings when she was growing up in Elliston.

“As kids, we hated them,” she said. “When you go inside there would be spiders. … Having said that, there’s much folklore around the cellars, about the young boys jumping out at the young girls and scaring them to death.

“(And) when you were a child growing up in Elliston, people would tell you babies came from roots cellars.”

Despite her early aversion to them, she was aware they were a curiosity for visitors to the area.

“There’s something about that dark hole in the hill, or the way the doors were there, there’s something attractive to the root cellar that always drew people,” she said.

Now Coles-Hayley is the chairperson of Tourism Elliston, and says the town began dubbing itself the root cellar capital of the world shortly after the cod moratorium in 1992.

“At that time, we had seen a lot of our residents have to pack up and leave,” she says, noting the population nearly halved in a couple of years, from 550 to 300 people.

Facing hard financial decisions because of a decreased tax base, Elliston went into the darkness, she says, when the town council shut off streetlights to save money.

Looking for ways to attract people to the area, they began paying closer attention to their small town, to see what they already had that made them unique.

“Early Newfoundlanders had to fend for themselves,”Coles-Hayley said. “Every season, there was something that had to be done in order for people to survive throughout the year. But what it all came back to was the root cellar that enabled people to stay here all winter long.”

They’re not certain their claim to being the root cellar capital of the world would get an official stamp, if such a thing existed.

“(But) it’s official as far as we’re concerned,” she said, laughing.

Because there was so little research on the topic, they couldn’t find anywhere else with so many root cellars in such a small area.

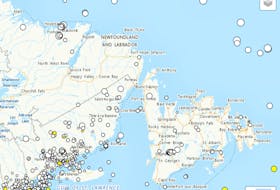

Now, there is more information available, after the Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador began documenting them 2010.

Folklorist Crystal Braye, who was pursuing her master's degree at the time, was part of that research, the process of which sounds easier than it was.

“I drove around and looked for root cellars,” she says. “They’re kind of disguised, especially on the Avalon, a lot of them are under sheds. I got ridiculously good at spotting them, actually. It took years for that to go away.”

Part of the research was simply speaking to people. Braye, who is originally from Brampton, Ont., says people were friendly, but often confused about why anyone was interested in them.

“One guy in particular, (he had) a hatch cellar, which I hadn’t seen any of at that point in time, so I got pretty excited about it, probably too excited about a root cellar,” she said. “He had a bucket, he was going to pick berries, and I stopped him and said, ‘Is that your root cellar?’ He was like, ‘Yeah, it is.’ I was like, ‘Can you tell me about it?’

“He looked at me like I had 10 heads and (said), ‘It’s where I put my potatoes.’”

People sometimes responded as if she was asking them what they kept in their refrigerator, Braye says.

As well, she heard stories from people who remembered them as kids, being asked to retrieve vegetables from the bug-ridden bunkers.

“I remember one woman telling me they had a hatch cellar. They had to lift up a hatch on the ground and go down a ladder,” Braye said. “She would stand on the hatch and jump up and down to get all the carpenters to drop off the hatch before opening it.”

But sometimes memories of them were a touch sinister.

“Some were threatened by it. They were told they’d be thrown in the cellar, so it’s kind of a scary place for children,” she said.

There was a more technical side to the research, too. They did architectural surveys, measuring the thickness of walls, GPS co-ordinates and what materials were used.

From that, she learned a lot, Braye says.

Typically, vegetables would be divided into their own wooden compartments called pounds. Often cabbages were stored up high, carrots and parsnips placed in bins or buckets of either sand or sawdust so they would stay firm and moist, and potatoes and turnips would be thrown on the ground or on a wooden pallet.

More people use them than some might think, Braye says, especially considering a renewed interest in sustainability, food security, eating local and reducing one's carbon footprint.

“Root cellars provide a great solution to a lot of those things,” she said. “When electricity and fridges became available, that was a sign of progress and prosperity, so using your root cellar was backward.”

But now it’s switching, she says.

“They’re gaining their respect back.”

@AndrewLWaterman