Growing up in the 1960s in remote Wabush, Labrador, I used to figure I was about as far away from war as one little fellow could get. As cub scouts, we all stood at attention in front of the town cenotaph, freezing, while images from Sargent Rock comic books, or photos from history books, drifted through my mind — anything to remind me of that war that took place “somewhere else,” somewhere far, far away.

That war, the Second World War, came much closer than I ever thought. It arrived about 500 short kilometres away, right on the coast of Labrador. It would become known as the only place in North America where armed German soldiers successfully landed.As it turns out, maybe not.

In 1943, Germany had just launched a new type of submarine, or U-boat. The XTC/40 was larger than former designs. Driven by powerful diesel engines it was capable of over 18 knots on the surface. Underwater power was provided by electric engines designed by Siemans-Schuckert, a company that would play a critical role in the only German armed landing in North America.

The Germans had a problem: accurate weather forecasting. Weather patterns generally moved west to east, and with their increasing U-boat activity around the eastern Atlantic, they needed more reliable weather information. The U-boats themselves could gather and transmit data, but to do so meant breaking radio silence, a potentially deadly activity that could betray their location. So German inventors developed another plan. It would be codenamed “Kurt.”

The Second World War, came much closer than I ever thought. It arrived about 500 short kilometres away, right on the coast of Labrador.

Kapitänleutnant Peter Schrewe was just 30 when he took command of the brand-new U-537, and the U-boat’s first assignment was a challenging one. He and his crew would become part of the Nazis’ solution. The answer was an automated weather station, one of several, designed by the German company Siemens. But it had to be placed somewhere remote, and the Nazis decided Labrador was the perfect spot.

It turns out they may have been working with inside information to decide on the location. In the “Them Days” publication titled “On the Goose” is a story about a Father “Schultz,” who, posing as a German Catholic priest, showed up on the Labrador coast back in 1933. As B.J. McQuaid writes, Father Schultz fit right in, travelling extensively by dog team along the coast of Labrador, pretending to be tending to his parishioners, while secretly taking extensive readings of weather, and charting details about the coastal topography. When war finally broke out, Father Schultz promptly disappeared. Later information surfaced that he may have escaped on another German U-boat or floatplane. There was also speculation that he had been a German flying ace in the First World War. The conclusion was that he had been a German spy all along, and that his information may have played a role in the mission U-537 was about to embark on.

U-537 left Kiel, Germany, on Sept. 18th, 1943 to head out across the North Atlantic. On board was the critical automated weather station they would attempt to install on the Labrador coast. It would not be easy. Allied forces were already well aware of the presence of German U-boats along the eastern seaboard. Not a year earlier one sank the SS Caribou, the ferry running between the Dominion of Newfoundland and North Sydney, Canada, and 137 people, including 10 children, lost their lives.

In the months that followed, over 40 more ships around the St. Lawrence would meet the same fate, including several near Bell Island. On March 3, 1942, a U-boat fired three torpedoes at the mouth of St. John’s harbour. Two struck the cliffs beneath Cabot Tower, breaking every window in the building. The other exploded at Fort Amherst.

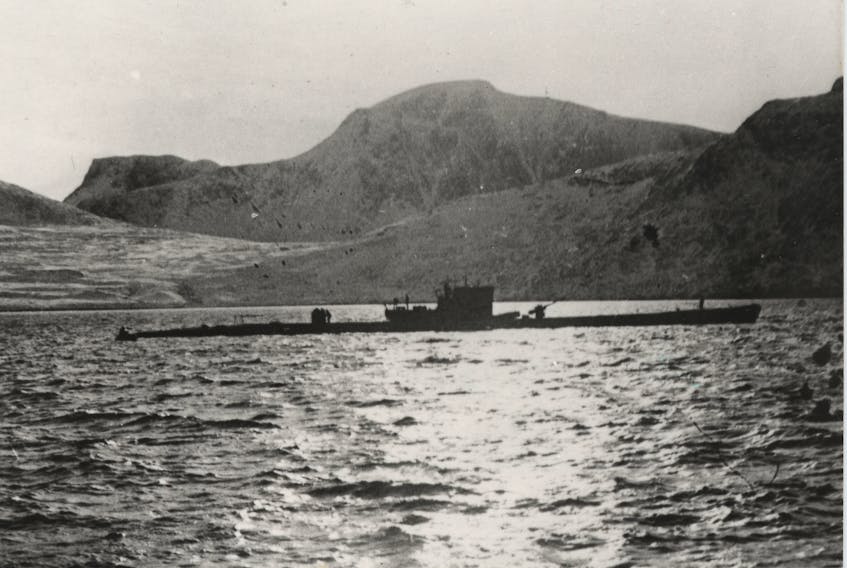

But even with advanced Allied surveillance in place, U-537 quietly made its way to the Labrador coast. On Oct. 22, 1943, it arrived in remote Martin Bay, a bare scratch of rock in the tundra, near the northernmost tip of Labrador. They dropped anchor and got to work. An armed team landed and spent the next 48 hours walking North American soil.

Aided by a German scientist sent along by Siemens, they Installed the automated system. Called the Wetter-Funkgergat Land (WFL), it consisted of 10 cylinders that looked, to all appearances, like a collection of oil barrels with an antenna. One barrel held the instruments. Many more held the nickel-cadmium batteries that powered a 150-watt transmitter. The station was capable of independently collecting and transmitting weather conditions, every three hours or so, during two-minute-long transmissions.

To try and hide the station, it was painted with camouflage. They even left empty American cigarette packets nearby on the ground, an attempt to fool any Allied forces that came across it. Painted on the side were the words “Canadian Meteor Service.” After ensuring it was working properly, the only known landing of armed German forces in North America was over. Now the young commander and his crew had to try to sneak back to base.

But on the way back, U-537 was detected and came under attack three times, including near Cape Race. Although slightly damaged, each time it managed to escape, and eventually it made its way back to the German’s big U-boat station in Lorient, along the coast of France.

It was a successful mission, but it would be short-lived. Within months, for reasons unknown, the automated weather station simply stopped transmitting. A second attempt to place another weather station on the Labrador coast failed, when the U-boat carrying it was sunk in the North Atlantic, off the coast of Norway, by the Royal Air Force.

U-537 did not fare much better. After being badly damaged on another mission and repaired, it was eventually reassigned to travel south, around the Cape of Africa to patrol in the far-off Java Sea. On Nov. 9, 1944, it was spotted and sunk with the loss of all 58 officers and men.

But amazingly, the weather station they had installed on the coast of Labrador sat undetected for decades. In 1977 Peter Johnson, a geomorphologist working in the area, found the station and assumed it belonged to the Canadian military. Over 30 years later, the German camouflage still worked! But it wasn’t until 1981, when the papers of the German scientist who originally helped install the weather station were examined, that the Canadian Department of National Defence was finally contacted with the truth.

Three years ago, this former Labrador Cub Scout saw it himself for the very first time, on display at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, a tangible reminder of the time armed German forces walked the ground, much closer to home than I ever thought.

Former CBC producer Reg Sherren is a freelance writer and author. His first book, “That wasn’t the Plan,” will be released in the spring of 2020.

RELATED