Whether John Cabot on his famous 1497 voyage from England actually first sighted land at Cape Bonavista has long been debated.

A Summit of the Sea Conference in the town of Bonavista in 1997 — as part of the 500-year discovery celebrations — concluded there was more evidence to back that claim than there was for other locations.

But the significance of Cabot’s “voyage of discovery” has lessened over time.

Cabot may have discovered new found land for England, but Newfoundland and Labrador — and the rest of North America – were never lost in the first place. They were occupied by Indigenous people.

History also outlines what the Europeans claim and occupation of Newfoundland and Labrador would mean for the Beothuk.

The unearthing of the Viking settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows on the tip of the Northern Peninsula revealed the Vikings were here 500 years before Cabot.

In any event, the Cabot voyages were important for England and have intrigued researchers for decades.

In recent years, historians from the University of Bristol — working on a major effort known as the “Cabot Project” — have uncovered new evidence surrounding the first English-led expeditions to North America hidden deep within huge parchment rolls, and only legible by using ultra-violet light.

Evan Jones, from the university’s department of history, nine years ago published a long-lost letter from King Henry VII that revealed that William Weston, a Bristol merchant, was preparing an expedition to the “new found land” with the king’s support. His sailing was to be a year after Christopher Columbus first landed on the mainland of South America and two years after Cabot reached North America.

Jones and fellow researcher Margaret Condon discovered information that Weston received a £30 reward from the king in 1500 as a contribution to the merchant’s expenses for his exploration of “nova terra.”

That new evidence came as a result of Condon’s painstaking work of trawling through official tax records, a news release states.

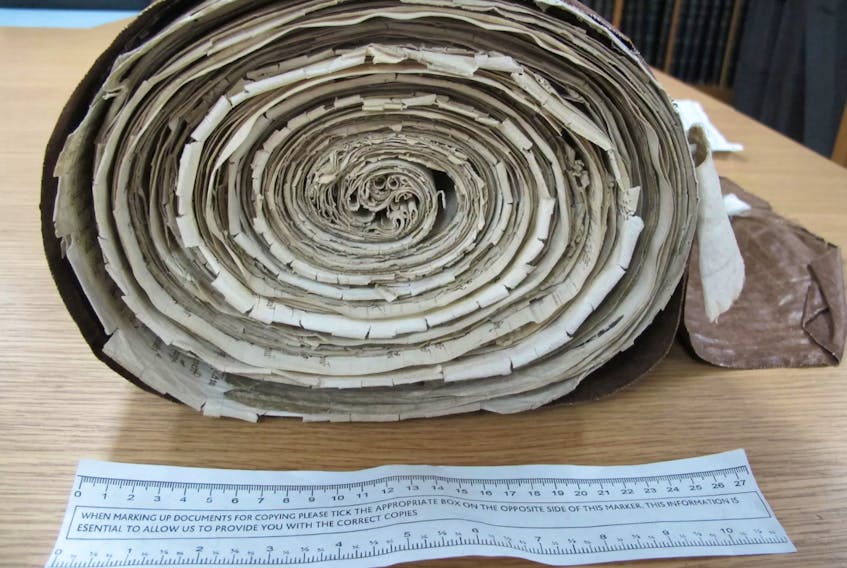

Each of the accounts take the form of a huge parchment roll made from the skin of over 200 sheep. Each membrane in the roll is two metres long and the new information found on it was passed over in the past, until Condon’s use of ultra violet light.

“First time I read the roll, I almost missed it,” Condon said. “These rolls are beasts to deal with, but also precious and irreplaceable documents. Handling them, it sometimes feels like you’re wrestling, very gently, with an obstreperous baby elephant.”

Jones and Condon published their work three months ago in the journal “Historical Research.”

They found that Cabot and Weston received rewards in January 1498, following an audience with Henry VII. This suggests the two explorers were working together long before Weston went on his 1499 expedition.

“The context for this research is that it forms part of a 12-year project to recover the lost research of Dr. Alwyn Ruddock of the University of London,” Jones explained in an email.

Beginning in the 1960s, Ruddock dominated research into the Bristol discovery voyages, making finds that promised to “revolutionize” the understanding of Europe's engagement with North America in the three decades after 1492. Ruddock never published her key findings, however, and prior to her death in 2005 ordered the destruction of all her work.

“I think we've now found over half the 23 'new documents' Dr. Ruddock had located between the 1960s and 1990s,” Jones said via email. “However, there are other documents that we have yet to locate.

“From a Newfoundland and Labrador perspective, by far the most important claim Ruddock made is that she said she had evidence that the friars who accompanied Cabot's 1498 expedition established a settlement and church in Newfoundland. If that was true, this church would be the first in North America, along with the first Christian settlement.

“Ruddock believed the settlement was founded at the site of the later community of Carbonear — the name being derived from the name of the church and/or the friar who established the community — Brother Giovanni Antonio de Carbonariis, who was from Milan. As I say though, we haven't found her evidence for this, so we can't confirm it. Also, I should stress that, even if Ruddock was right, the settlement could only have lasted a few years before being abandoned.

“Ruddock also suggested (Weston’s) voyage took him north up the coast of Labrador as far as the entrance to the Hudson Strait — presumably in an attempt to locate a sea passage around America and on to Asia. So that would make it the first Northwest Passage expedition. Again, though, we have yet to locate the clinching bit of evidence she seemed to have located to prove this.”

Jones and Condon’s research is continuing. They say they are excited as to what they may uncover as they attempt to follow Ruddock’s claims and journey into new areas.

“I think we’ve got well over half of the documents Ruddock located, but there are definitely more, especially in Italy,” Condon said. “She did a lot of work there, including in the private archives of some of Italy’s great noble families.”

Jones and Condon say Weston was likely one of the unnamed “great seamen” from Bristol discussed by Italian diplomats and merchants in the winter of 1497-98.

They say letters the Italians sent back home from London confirm Cabot had Bristol companions on his 1497 expedition.

The outcome of Cabot’s final expedition in 1498 is unknown, and it is unclear whether any of the ships returned.

Jones and Condon say that may explain King Henry’s willingness to send another expedition the following year, led by one of Cabot’s deputies — Weston.

“Cabot’s voyages have been famous since Elizabethan times and were used to justify England’s later colonization of North America,” Jones said. “But we’ve never known the identity of his English supporters. Until recently, we didn’t even know that there was an expedition in 1499.”