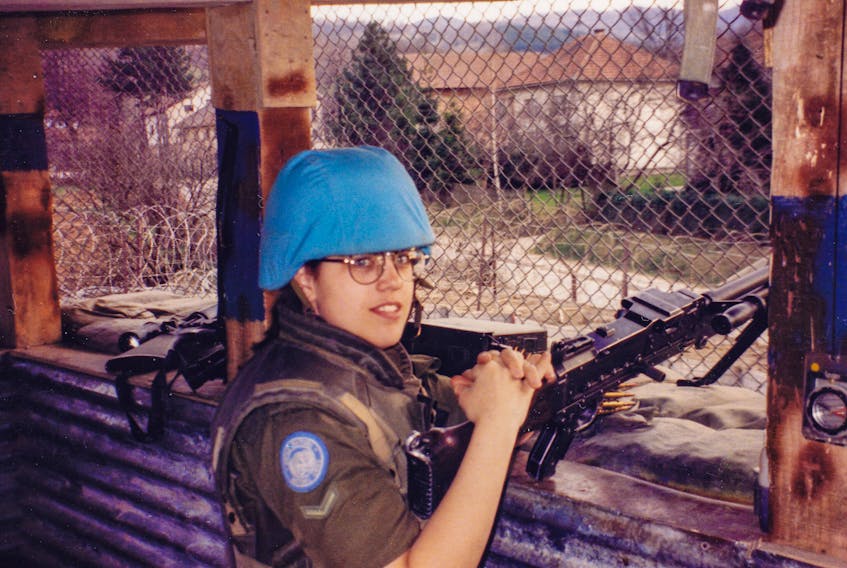

In October 1993, Lesleyanne Ryan of Mount Pearl was one of 150 Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) personnel posted to Bosnia. At the time, the mostly Muslim population of Srebrenica was under the protection of the United Nations.

While delivering supplies to Srebrenica, one of Ryan’s friends met a young boy.

“(His family) needed extra help,” she said. “A lot of the aid was being stolen and warehoused. … It wasn’t getting to the people.”

She gave whatever she could — bars, tinned food — to help the boy.

“In March, the Dutch had agreed to take over with 800 troops,” she said. “(My friend) went up with his last bit of food for the boy and came back with two licence plates — one for him, one for me — that say Srebrenica.”

“It took months for the story to really, really come out. And then I read a comprehensive report of exactly what had happened. It was horrifying.”

Ryan was posted to Halifax in the summer of 1995, as the genocide began.

“I was getting the news piecemeal as I was settling into my new place,” she said.

All she could think about was the boy.

“It took months for the story to really, really come out,” she said. “And then I read a comprehensive report of exactly what had happened. It was horrifying.”

Ratko Mladic, military commander of the Army of Republica Srbska and now a convicted war criminal, had promised the people peace. Between 25,000 and 30,000 civilians, mostly women and children, were bused from the area, leaving 15,000, mostly men and boys.

The offer of peace was a lie. More than 8,000 Bosnian Muslims died trying to escape through the woods. Their bodies were dumped into mass graves, and later moved to a second location in an attempted cover-up.

Ryan scoured the Red Cross lists trying to find the boy, but never did. She likes to think he is still alive, and about 40 years old.

Ryan retired from the CAF in 2002. She began studying for an English degree in 2004 and concentrated on finishing a book.

Released in 2010 "Braco," meaning "little brother" in Bosnian, is a fictional story that takes place in the five days after the genocide began.

It follows six different characters, including a young boy and his mother.

“All the events that happened around those characters were real,” Ryan said.

Writing it became therapy for her post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), she said.

War was nearby

When Yugoslavia began falling apart in 1991, Eldin Husic, a 15-year-old cadet in the Yugoslavian army, and his unit, was called to Serbia.

“The former Yugoslav army, that used to represent six provinces, plus two regions, gathered together in one region in Serbia,” said Husic, who now lives in St. John's.

But Serbians, Croatians and Bosnians started to splinter.

“At one point, the army asked me, ‘Who are you?’ I said, ‘I am a Yugoslav.’”

He was told there were no Yugoslavs anymore — he was either a Muslim, an Orthodox Christian or a Catholic.

Husic has both Muslims and Roman Catholics in his family. Since his name was considered Muslim, that’s what he had to declare.

“In '94, I was actually expelled from the army,” he said. “Even though I became an officer, I could no longer be there because I was a Bosnian Muslim.”

He says while the genocide was happening, he lived with Serbs in the town of Šabac.

“From ’94 to ’96, I was persona non-grata. I didn’t exist,” he said.

“One hundred kilometres away we lived in this paradise, while this was happening just across the river.”

Feeling like a refugee in his own country, he would spend his summers swimming in the Drina River, which he calls the bloodiest river in that country.

“Massacre, just massacre,” he said of the bodies discarded there.

He travelled with a punk rock band as a roadie and would tell people his name was Ivan.

“Nobody would ask me (if I was Muslim), this long hair guy, smoking cannabis, carrying guitars. … The band was half Croatian, half Serbian. Everything was such an idiocy.”

The mentality of the Serb army at the time, he said, was, “No Muslims, no problem.”

“I thought the Bosnian Muslims were horrible, (that) they were provoking Serbians,” he said.

In 1996, Husic emigrated to St. John’s. A couple of years later he became a Canadian citizen.

“I was afraid of going back. I was pro-Serb. I thought if I go back to Bosnia, they’ll kill me,” he said.

It wasn’t until 2001 that he returned to visit his family. While there, his father’s friend began telling stories from the war. Husic said he almost fainted.

“This is when I realized I was living a lie. This is when I realized what happened in Bosnia. This is when I realized Srebrenica happened.”

He had been indoctrinated, he says. He now knows it had all been planned, something upheld by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, when it ruled in 2001 that what occurred in Srebrenica was genocide .

Now, Husic owns the Balkan Kitchen in downtown St. John’s. Though it’s been a quarter of a century, he thinks about that time “every time I go to sleep, every time I wake up, everything I do is about it.

“I’m (speaking about it) for those of us who can tell no tales, people (who) had dreams … ideas.”

On assignment

St. John's photojournalist Greg Locke, after his assignment for Maclean’s and Reuters in Bosnia was finished, decided he was going to stay.

“It was a part of the world I hadn’t been in before, I had the contacts, I had the way to do it, I had the money, so I stayed,” he said.

Locke, who was 36 at the time, landed in the former Yugoslavia after the genocide had taken place, to cover the end of the war and the Dayton Peace Accord.

“They knew there were mass graves there, (but) they couldn’t find them. I spent a lot of time in helicopters with the British Navy, flying … looking.”

“(The war) was still pretty hot, there were still landmines everywhere, you still had to watch yourself when you travelled, there was still a lot of animosity between the different groups,” he said.

Buildings continued to burn, and gunshots continued to resound.

“They knew there were mass graves there, (but) they couldn’t find them,” he said. “I spent a lot of time in helicopters with the British Navy, flying … looking.”

Locke says it’s hard to believe it’s been 25 years. And while the flashbacks are there all the time, there are never any regrets about working there, he said.

The genocide in Srebrenica ended on July 22, 1995.

On Friday, the provincial government proclaimed July 11 as Srebrenica Remembrance Day.

[email protected]

Twitter: @AndrewLWaterman