My father’s favourite song was “Saltwater Joys.” After he died, we sang it at his funeral, and then we buried him in a Newfoundland bog.

Aside from a brief stint as a student in New York City, which he called “the pits,” my father never wanted to live, barely even wanted to be anywhere else. He was happiest out on the water or sitting back and having a drink under the Newfoundland sky.

He probably could have lived anywhere in the world, but he chose to stay. He made less money, but he wouldn’t even think of living anywhere else.

When I moved back home in 2011 to have my son, I had the same attitude. Like Vickie Morgan, who recently wrote an essay for the CBC called “I’d rather starve in Newfoundland than live anywhere else,” I had no job, but bit by bit I coaxed my husband up from the States. He gave up a tenure-track job to live here, on the island, because I needed to be here. I needed to raise my son here. My husband called me a salmon who needed to go back home to spawn.

We made it work, for a while.

•••

Then came word of economic woes. Oil prices collapsed. Muskrat Falls disaster. This was a familiar refrain. I had grown up during the collapse of the fishery in the 1980s in Newfoundland. Everything was doom then, too. I was my father’s daughter; we could figure it out.

But over the course of the next few years as I took meetings with people who were sympathetic but powerless to offer me work, after crying in meetings, after being met with silence from people who wouldn’t even respond to my request for meetings, I had to face the facts that so many Newfoundlanders have had to face over the years.

We can’t figure it out.

I had to face the reality that many of my cousins — who now live and are doing well all over Canada — had to face all along: it is just not possible to build something on an island that is not looking for new ideas or ways to help young people, or their children, stay.

•••

I know that when people say they will stay against all odds that they are reacting against a rhetoric of inevitability. They want to repudiate the rhetoric of outmigration we all grew up with. They want to respond, forcefully, to an island and a world that tells its young people that they have to leave, that they cannot stay.

But the truth is that it is no more heroic to stay than it is to leave and do what needs to be done for one’s family.

It takes strength to say it is time to go — to one day pick up your bags and sell all your books and pile your six-year-old son, who is named after your father, and who is wearing a Leonard Cohen fedora, into your mother’s car and catch a plane to Montreal.

This is also a part of the island’s story.

•••

I had forgotten that my father and my mother and their entire families had already been displaced years before when they left the outports. They never went back. They couldn’t. There was nothing left for them there.

Migration, whether fleeing war or economic collapse, is almost always the story of people doing what they must. We leap into the unknown in order to survive, and that takes courage, too.

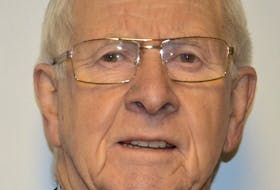

Robin Durnford is the author of three books of poetry: “A Lovely Gutting” (2012), “Fog of the Outport” (2013), and “Half Rock” (2016). She currently lives in Montreal.