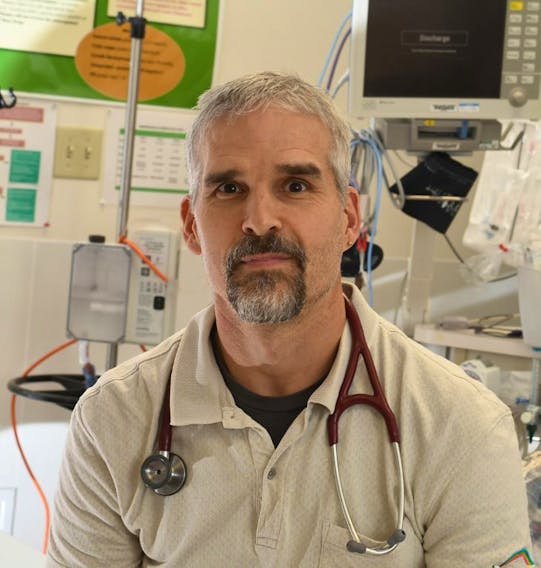

DR. CHRIS MILBURN

There is something that I need to speak out on before it's too late. I was prompted to write this by the high-profile case of the two Halifax special constables who were convicted on Sunday of criminal negligence causing the death of a man in custody.

As an emergency physician, I have a strong connection to this issue, and this court case makes me shudder.

The starry-eyed view of medicine is that we spend our time helping appreciative people who are polite and reasonable. In reality, on a very regular basis, we deal with "the criminal element." Through my 20 years working in emergency departments, people have taken a swing at me, I’ve had my shirt ripped off, and I’ve been spit on numerous times. I have been told “I know where you live” (probably true in our small community) and physically threatened.

I have seen criminals spit at, assault and threaten officers and the officers’ families. I am constantly amazed by the grace, compassion, and patience shown to these patients, which often exceeds that from our physicians and hospital staff.

I was taught to respect authority and take responsibility for my own actions. As such, I have always had great respect for police and related professions. My respect has only grown during my many interactions with them and jail guards during my work. On at least one occasion, I am quite sure they saved me from grievous harm (or worse) when dealing with a particularly violent criminal.

The ED has always dealt with people involved in altercations, stabbings, domestic assaults, etc. This is not new. But the amount of ED resources being taken up by criminals has been on the rise. In the last decades, there has been increased scrutiny on police, and new rules dictate that they have criminals “medically cleared” before locking them up. Anything bad that happens to a criminal now seems to be the fault of the police, and not the individual under arrest. Police policy here in Nova Scotia now mandates that any person under arrest about whom officers have any medical concern must be brought to emergency for “medical clearance.”

How does this policy translate in practice?

It is the patients who are too violent, refuse to be honest, and are the most wild-behaving and impaired that have to be brought to the ED for “clearance.” This means that screaming, spitting, potentially dangerous people are now brought to EDs for doctors, nurses and support staff to deal with. It is much too dangerous for a blood collector or nurse to approach the patient with a needle, as this puts patient and staff at great risk for injury.

Spit hoods sound cruel and unusual to someone who has never been around one of these patients. But it is not safe, nor reasonable, to expect police, jail guards or hospital staff to be spit on as a normal part of their job. A large percentage of patients who would spit on someone trying to help them are carrying dangerous infectious diseases.

REACTION:

- DR. CHRIS MILBURN: It's not fair for critics to question my compassion or professionalism

- DR. JULIE CURWIN: Why Dr. Milburn's salvo against 'victimhood culture' went viral

- STEVE BARTLETT: ER doc’s commentary reaches hundreds of thousands

- DR. ARUNA DHARA & DR. LEAH GENGE: Patients need care, not condemnation

- CHRISTINE COOPER: Memo to Dr. Milburn — people in crisis no less worthy

- LETTERS: 'Criminal element' in ER — readers react to Sydney doctor

- MARYN MARSLAND & ALEX STRANG: Blaming patients unseemly — criminal behaviour often a byproduct of social ills

- Under attack: Doctor says abusive patients creating critical situation in P.E.I. emergency department

I am quite convinced that if we could share video of these interactions, the public would be much more sympathetic to police and hospital staff and their conundrum.

Meanwhile, the poor old lady with cancer trying to sleep in the next room is woken up by screaming and profanity. All the waiting room patients are held longer as we deal with police and patients coming through the back door. Police who should be patrolling our streets are stuck in an ED waiting with the patient.

So where does this leave me? I make my best judgment after getting as much information as I safely can. I usually sign the form. Off they go to lockup. Over the years, I have done this God knows how many times. So far, nobody I have sent to lockup has died.

I don't say this to pat myself on the back. I’ve mostly been lucky. One day, one of these criminals will have taken a drug, or drug combination, that will kick in later. He will have swallowed a baggie of cocaine that will later explode and cause an overwhelming overdose. One of these times, my luck will run out.

Then they will come for me.

So I’m speaking out about this now.

I don’t think the general public has any idea of how many thousands of these patients/criminals go through our jails and EDs in the run of a year. Given how difficult they are to safely manage and assess, it is amazing to me, and a testament to just how good our system actually is, that such a tiny percentage of them do die while in custody.

It’s also important to keep in mind that for every one of these people who dies in custody, many times that number die in flop houses, alleys or at home. Being arrested is the safest thing that could possibly happen to them.

Police and jail guards have great power. They must be held to a high standard, and I believe they already are. They should not be held to an impossible standard. We can never create a perfect system that locks up dangerous, intoxicated criminals and protects the public from violent criminals 100 per cent of the time, yet never have one of these criminals die in custody, ever.

It’s not possible.

In our quest to create this unachievable perfect system, we will use an incredible amount of resources. Use of tax money is a zero-sum game, and for every extra dollar we put to making violent criminals safer, your grandmother waits longer to have her hip replaced.

In medicine, we joke that the most accurate diagnostic tool is the "retro-spectroscope." It is easy to play armchair quarterback. The public can now look at slow-motion video of a police takedown and say what an officer should and shouldn’t have done, whereas the officer had to make the call in real time. They can judge a system based not on the 99.9 per cent of cases that worked out safely, but the 0.1 per cent that ended badly.

“Hard cases make bad law,” as they say. We should look at how this system functions overall, consider how often it works well vs. how badly, and make reasonable decisions based on that balance. More knee-jerk policy based on the ridiculous idea that we can create a system where no intoxicated violent person EVER dies in custody just creates unreasonable demands on health care and justice, taxing already strapped systems. Blaming those of us who try so hard to protect the public (and the individual himself) from dangerous criminal behaviour is destructive to our future direction as a society. Maintaining that the criminal himself is primarily responsible makes it more likely that we will see a decrease in this type of behaviour.

"First they came for the jail guards, and I said nothing because I was not a jail guard.

Then they came for the police, and I said nothing because I was not a police officer.

Then they came for the doctors, and there was nobody left to speak for me."

Dr. Chris Milburn is an emergency room physician in Sydney. These views are his own.

RELATED: