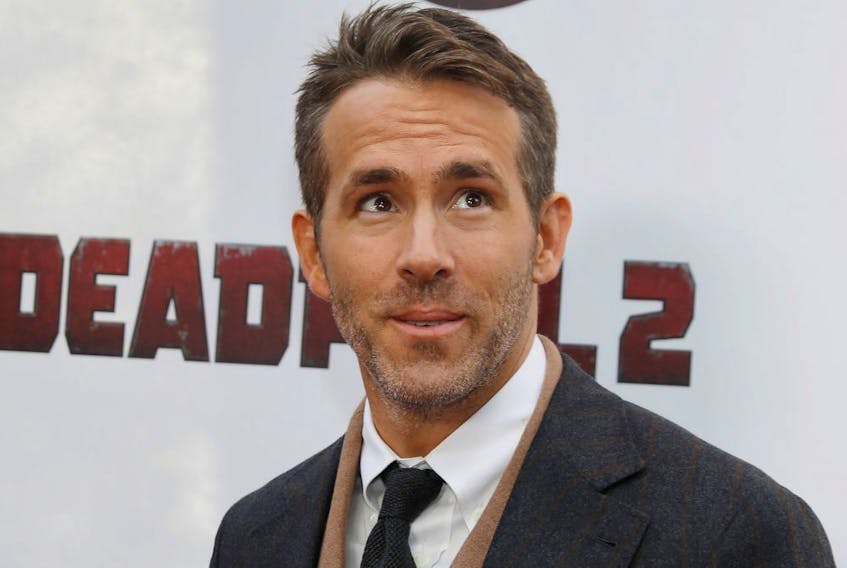

I’m a little scared for actor Ryan Reynolds. And for his business partner Rob McElhenney, whose uneven but brilliant show “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia” I happened to discover under pandemic conditions. This week, the celebrity pair nearly completed their purchase of a Welsh soccer team, Wrexham AFC, which currently competes in the National League, the fifth-highest level of the English footballing pyramid. (Wales has its own governing body and pyramid of leagues, but there is some crossover in both directions, and the biggest Welsh teams play under English auspices.)

Reynolds is not the first Canadian to take a stake in an English football club; the Alberta sheik Brett Wilson had a piece of Derby County FC for a few years. But in general the Wrexham purchase has been a head-scratcher for the local supporters and for the English/Welsh football scene.

The club, considered the world’s third oldest, had been owned by a fan trust since 2011. Fan ownership is financially limiting, but according to a pretty thorough analysis by BBC Sport Wales’s Michael Pearlman, the trust had not been actively seeking outside investment despite a long decline. At the turn of the century Wrexham was an established tier-three club; the National League is considered to be outside “league football” altogether (confusing, ain’t it), and even at that level Wrexham is struggling.

Ryan ‘n’ Rob don’t have any particular connection to Wrexham, and despite its antiquity the team doesn’t even have the slender international following that some minor British teams have. Welsh expatriates are probably more likely to be breaking their own faces on a rugby pitch than obsessing over a soccer club from back home.

The pair seem to have conducted a scan of affordable western European soccer clubs and decided that Wrexham fit their criteria — but since they’re both comedians, doubt and confusion about their intentions is natural. They admit to not knowing the game well, but have done an excellent job reassuring everybody. Deadpool and Mac needed to win a trustholders’ referendum to complete the sale, and got 95 per cent of the vote.

Reynolds already has a history as a successful investor, and as a pure business proposition this foray into Wales does make some sense. North Wales and neighbouring Cheshire have enough people and enough money to be able to support a half-decent football club, if not a top-tier contender, but nobody is occupying the void. The profile of Reynolds and McElhenney has already led to a spike in “Wrexham AFC” Google searches, and they cut a funny fish-out-of-water commercial for the team’s chief sponsor, the (large) Welsh trailer manufacturer Ifor Williams.

Interested Americans will have infernal trouble finding TV broadcasts of the club’s matches, but a documentary, if they felt like making one, could make back their promised £2-million investment immediately. At the level Wrexham is at, this kind of cash would make the club an instant candidate to return to league football. (At a top-flight club it might not cover the salaries of the nutritionists.)

The potential upside might as well be infinite, although celebrity owners of English football clubs have a mixed track record at best. Reynolds and McElhenney want Wrexham to become a “global force,” but they don’t need to be remotely that successful to come out ahead.

What they do have to do is navigate the culture of British football — the culture of Britain, that is, which in all four of its national manifestations has a vicious, unforgiving side. Rich men have often dumped money into English football teams expecting to be able to control them or modify them in their own image. But ownership of a British football club simply doesn’t denote the same concept as ownership of an NFL or NHL team does.

Yorkshire-born businessman Assem Allam was lauded to the skies when he bought Hull City AFC in 2010, pumped money into the club and took it to European competition and an FA Cup final. But Allam wanted to rebrand the team as the Hull Tigers because he felt, very strongly, that the word “city” was the hallmark of a lame soccer enterprise (you know, like Manchester City).

This led to derision and rage, and the people of Hull went behind Allam’s back to persuade the Football Association to forbid the name change. Allam, as if determined to make matters worse, argued that the supporters ought to be grateful for his money if they wanted attractive, successful football. It turned out the fans cared more about Hull City AFC continuing to be that, and not something else. The chants grew louder and meaner. Allam turned off the tap. Hull City, which he still owns, is in free-fall.

Something similar happened in Wales when a new co-owner of Cardiff City FC, Vincent Tan, tried to change the team’s home kit from blue and white to red and black. Tan vowed not to back down, but restored the old home colours after a few years of continuous abuse.

Canadian hockey fans understand this sort of fan-owner warfare over trivialities, but we are not one-tenth as serious about it as the British. The characteristic structure of North American professional sports makes business considerations paramount over traditions, and we recognize this consciously.

What we overlook is that guaranteeing true success to only one championship-winning team a year puts fans in a position of inherent desperation and subservience. There are 100,000 people in Edmonton, possibly including me, who would kiss the heinie of the Oilers’ owner for a Stanley Cup. Lord knows quite a few do it, anyhow, when the team stinks.

Outside of Montreal, we will, ultimately, tolerate an obnoxious change of team sweaters or colours or insignia. The attachment of British people to their penny-ante football clubs is more like our attitude toward the Stanley Cup — and even when it comes to the cup, the only national regalia we possess, we’ve been mighty backward in defending it from exploitation by businessmen.

Allam’s idiot struggles over the word “city” have guaranteed him 100 years, without exaggeration, as a punchline and an object of hatred in his own birthplace. It seems unlikely he would repeat the experience given the chance.

This is the sort of risk Reynolds and McElhenney are taking. If they arouse fan ire by making an inappropriate or inadvertently insulting move as owners, there will be blowback on every conceivable level. The producers of “Deadpool 3” will find themselves wondering why they’re being treated in Wales the way the city of Liverpool treats the Sun newspaper.

The duo is obviously aware of this, having been careful to promise that Wrexham AFC will not “be relocated, renamed, or rebranded” under their stewardship. But there are 100 other missteps that could lead to sneers, chants and, in the worst case, boycotts from the faithful. You don’t really “own” an English or a Welsh football club; you’re just renting the leftover profits, if there are any, which nine times out of 10 there aren’t. Good luck, fellas.

National Post

Twitter.com/colbycosh

Copyright Postmedia Network Inc., 2020