There was always a big problem with the decision to launch an impeachment drive against President Donald Trump. That is: the end was evident at the beginning. The Democrat-controlled House was always going to vote to impeach; the Republican-controlled Senate was always going to keep Trump in office. The hearings are over and nothing has happened to change that.

So why did Nancy Pelosi go ahead with it? We know she was reluctant: she stalled and stalled for quite some time, well aware of the situation with the Senate and hesitant to feed charges her party had become fixated on Trump at the expense of all else. Perhaps the sheer hatred of Trump within her caucus simply became too much to resist. But she must have known the risks were high and the odds of success low.

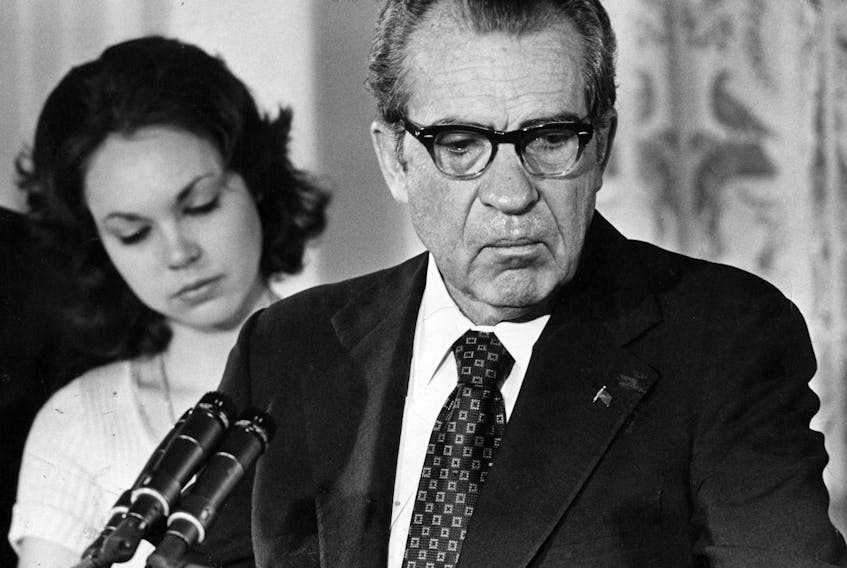

To succeed, she had to confront a largely indifferent American public with evidence so overwhelming it could pierce deep layers of cynicism and distrust. Many comparisons have been made between last week’s public hearings and the televised Watergate investigation that galvanized the country and brought down Richard Nixon. Democrats had to recreate those conditions if they hoped to force Trump’s departure. They didn’t come close, and there are several reasons why.

Perhaps the biggest is the difference in public temper. Americans in 1972 were shocked by what they learned about their president. No one is shocked by Donald Trump any more. Everything Trump is accused of is completely within character, as he continually reminded the world throughout the hearings with his barrage of tweets, denials and new insults, fired off even as witnesses were still giving evidence.

To succeed, she had to confront a largely indifferent American public with evidence so overwhelming it could pierce deep layers of cynicism and distrust

Democrats would have loved to have found a John Dean within the Trump camp, but had no such luck. Dean was the White House counsel who dealt directly with Nixon and had first-hand knowledge of his actions, and agreed to testify against him in return for a plea bargain on his own involvement. His presence at the scene of the crime gave him great credibility in convincing people of the truth of his claims. Pelosi’s forces couldn’t muster anyone as weighty. Even the original Dean — now 81 — thought Gordon Sondland, ambassador to the European Union, might fill his role. But while Sondland’s testimony was compelling in many ways, he lacked Dean’s depth of access to Trump and had to acknowledge he was never specifically told by the president that $391 million in aid for Ukraine was being held up until he got the dirt he wanted on Joe Biden. He just “presumed” that to be the case based on the fact it was dead obvious from Trump’s words and actions.

Though Nixon was a polarizing figure in his day, he had a much greater claim on respectability than the current president. He’d been vice-president for eight years under Dwight D. Eisenhower, came within a few counties of besting John F. Kennedy in the 1960 presidential race, staged a triumphant comeback and won re-election in 1972 with 60 per cent of the vote and 49 of the 50 states. He’d opened the door to China and moved towards peace in Vietnam. While that record won him the benefit of the doubt with a lot of Americans, it also made the eventual revelations that much more damning. Nixon’s admirers believed in him and were offended when they learned the truth; once opinion shifted it shifted sharply. Trump’s fans don’t care if he was right or wrong; his ratings haven’t budged an inch.

Which raises the question again of why Pelosi gave her blessing to the hearings, when even the timing was weighted against her. The Watergate scandal played out over two years, between the June 1972 break-in and Nixon’s 1974 resignation. Those 26 months were filled with a succession of news shocks, revelations, drama and high politics. The change in public opinion developed over time as people absorbed the unfolding events and came to grips with them. Reality TV hadn’t been invented; watching it all play out live from the living room sofa was a new experience.

Trump’s case has none of that. He was, after all, a reality TV star, what else did anyone expect? If his faithful flock wasn’t perturbed by dalliances with a porn star, why would they care about putting the squeeze on Ukraine?

By the time Democrats launched their case, they were up against the clock. The drive to have an impeachment vote by year-end forced the hearings into a few weeks in the final months before primaries are held for the 2020 election. Their case against Trump isn’t criminal, but political — to succeed they had to make it impossible for Republicans to defend him any more, as the revelations against Nixon did. Absent a recording of Trump ordering Rudy Giuliani to go bribe the Ukraine president, it’s difficult to conceive anything that could achieve that in today’s atmosphere. Would even that have been enough? It’s a legitimate question.

Perhaps Pelosi and her crew simply hoped to further tarnish Trump’s presidency as candidates vie for the nomination to challenge him next November. Or they feared history might look back in the future and ask, how could you let this go on without acting? Perhaps. But it takes more than an odious personality for Americans to sanction the early eviction of a president. That takes an election, and Democrats had best be better prepared when that rolls around.

Copyright Postmedia Network Inc., 2019