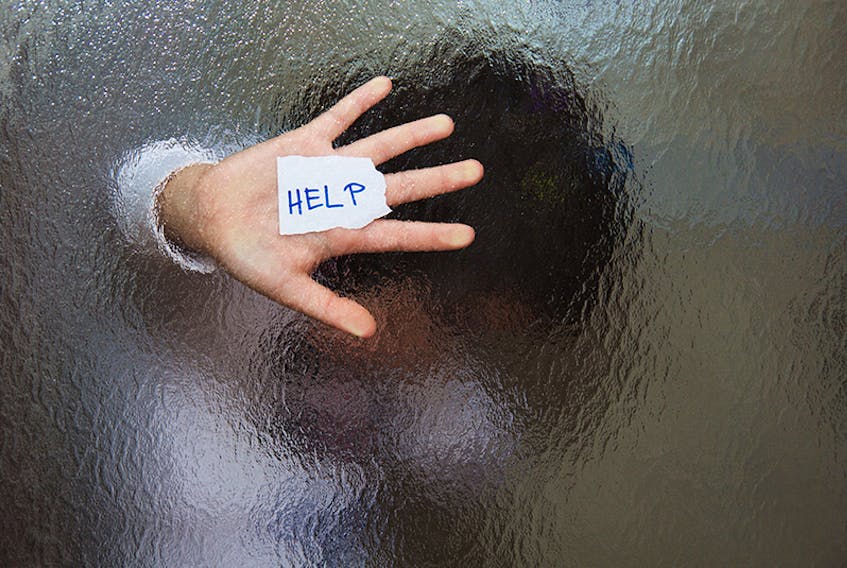

Secrecy used to be paramount for transition homes offering shelter to women and families fleeing domestic violence.

Where these homes were was confidential, to protect fearful residents from abusive, controlling men who might seek to punish their partners — or those helping them.

But that’s been changing, say transition home officials.

Quick aside. This is a follow-up to last week’s column on domestic violence that flowed from a conversation I had with Shiva Nourpanah, co-ordinator for the Transition House Association of Nova Scotia, and Helen Morrison, executive director for the Cape Breton Transition House Association.

There are a number of reasons many transition homes across North America are now publicizing their location.

First — and critically — these days many transition houses have state-of-the-art security, including multiple cameras and other layers of protection.

There’s also evidence, says Morrison, that once their locations have been publicized, transition homes can count on neighbours to also keep watch, for example by reporting unknown men lingering near the facility to police.

The location of Willow House in Sydney isn’t publicized, says Morrison, but neighbours who know it’s a transition house are similarly protective.

Second, women desperately seeking refuge too often don’t know where to go.

Many live outside bigger communities where transition houses are often based and don’t know the home’s local area. So, even with written directions, finding it can be a challenge.

“We had a woman, two years ago, who came to us, knocking at the door, needing our support,” says Morrison. “Thank goodness it was the summer.

“She had spent the night asleep ... in the park here in Sydney, which is very close to our shelter. She didn’t know where we were. The next morning, she went to a local convenience store and said: ‘Do you know where I can go to get shelter? Do you know of any transition house?’ or whatever, and the person there said, ‘Yeah, it’s right there.’”

For women living in fear, their movements restricted by an abusive partner, even getting basic facts about a local transition home can be daunting.

“A lot of the people who don’t have the information are the people who are living and experiencing it. And that’s because they’re controlled; what they know and what they hear is controlled,” says Morrison.

Last, secrecy itself has traditionally often been associated with shame.

Even in the 21st century, women may still be asked what they did to provoke their partners, as if it’s somehow their fault they’ve been the victim of domestic violence.

Nourpanah says each transition home individually decides on the question of location confidentiality. Morrison says her association is now discussing the issue.

But the trend has been toward greater transparency.

For women living in fear, their movements restricted by an abusive partner, even getting basic facts about a local transition home can be daunting.

I want to pivot to one last topic we discussed — lasting solutions.

That women, here in the 21st century, must still sometimes flee for their lives — at times, tragically, unsuccessfully — to escape a violent, controlling partner is far beyond sad.

It’s likely too late to alter the mindset of hard-core abusers, especially as they get older. In such cases, an effective, vigilant justice system, backed by a watchful community and properly funded transition homes, may be all that’s realistically possible.

If there’s lasting hope for change, it’s in younger generations.

I’d like to see core curriculum teaching children, from a very young age in schools, conflict resolution, mutual respect, healthy relationships, wellness, etc., along with — at an appropriate grade level — how to find help if needed and the legal consequences of being an abuser.

Transition homes and other violence-against-women organizations do run some of these types of programs in schools and in social education programming, says Nourpanah.

But they’re very project-funded, which is typical in this sector, she says. When the money runs out, the programs end.

“It should be, absolutely, an ongoing part of education, you know, how to behave and healthy relationships and red flags,” says Nourpanah. “All that.”

At the same time — and to repeat a point made in last week’s column — both Nourpanah and Morrison stress that domestic violence is part of a broader societal problem.

“There’s so much going on with male violence, whether we’re talking about media depictions and the glamourization of male violence, or whether we’re talking about the particular stressors that are gendered, that men and women have differently, around unemployment, around finances, that kind of thing,” says Nourpanah.

“There’s a lot that needs to be done on a social, cultural level.”

“The changes we want to see in the world? They’re probably not going to happen in our lifetime,” says Morrison.

“But, boy, if we can help to instil some of that in our children, and then they will instil that in their children, then the future looks better.”

If you are seeking help or are looking for information about abuse, you can call the Transition House Association of Nova Scotia’s 24-hour toll-free line: 1 855 225 0220.